At the start of this new year, the Womble Bond Dickinson Insurance Team review recent developments in the insurance arena and look forward to what 2019 may bring. In this article, we touch on a wide range of developments and potential future issues in professional negligence claims against solicitors, surveyors, tax construction and pension professionals, insurance brokers and IFAs. We also take a look at claims against Directors and Officers and provide commentary on developments in cyber claims. Our US colleagues provide insight on developments in claims against Directors and Officers in 2018. Finally, we consider the implications of Brexit for insurance companies.

We are also delighted to bring you a costs update from guest contributor Simon Noakes.

At the start of a new year characterised by huge political uncertainty, any hope that 2019 will provide a more stable outlook for the insurance sector is likely to meet with disappointment. With Brexit issues unfolding/unravelling by the day and the global economic climate moving in the wrong direction, we expect to see a significant shift in the outlook for insurers in professional indemnity, D&O and cyber over the coming year.

Solicitors

2018 saw the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court grappling with a number of issues arising from a range of solicitor practice areas.

Cannibalism and loss of chance

In recent years changes to both the costs regime in respect of personal injury claims and the recoverability of CFA success fees has had a significant impact on claimant firms working in that area. This has seen a shift by such firms to the potentially more lucrative field of professional negligence, pursuing claims for under-settlement of exactly the type of litigation that they once pursued: a phenomenon that has come to be known as "cannibalism."

A particular line of authorities has developed in this area out of the scheme introduced by the Department for Trade and Industry (DTI) in the late 1990s in order to compensate former coal miners employed by British Coal who contracted vibration white finger (VWF), an industrial disease linked to the use of vibratory tools. A number of appellate decisions have arisen from cases alleging that claimant solicitors under the DTI scheme failed to adequately advise on potential special damages claims, in respect of basic household chores such as window cleaning and DIY, that claimants were prevented from doing as a result of their VWF.

That line of authorities has proved extremely claimant friendly, imposing a substantial burden on solicitors to challenge client instructions regarding settlement and to ensure that the full implications of their decisions are understood. While the Court of Appeal's decision in Thomas v Hugh James Ford Simey [2017] EWCA 1303 did suggest a relaxation of the duty to take account of cases that are low value/high volume, and often carried out on a fixed fee, we have not so far seen the impact of this flow down to lower court decisions.

Perhaps the most significant recent decision in this area, and one of broader interest to professional negligence claims generally, has been Edwards v Hugh James Ford Simey [2018] EWCA Civ 1299. At its heart, this case reinforces the point that in claims against a solicitor for the lost opportunity to pursue litigation, the court will: (i) not conduct a trial within a trial by looking at the underlying claim in great depth; and (ii) in assessing the value of that lost opportunity, only look at the evidence that would have been available at the notional date of trial, rather than considering new evidence obtained with the benefit of hindsight. In Edwards, the Court of Appeal held that it was inappropriate to have regard to expert medical evidence concluding that the Claimant did not in fact suffer from VWF. Accordingly, a Claimant might still be entitled to compensation in respect of a medical condition that he did not suffer from. While at first blush this might appear counter-intuitive, the rationale behind this approach is to allow the court to accurately assess the value of what a claimant has lost and the prospects of that outcome being realised. At the time of the Defendant's advice the Claimant had supportive medical evidence and the nature of the DTI's scheme was such that this was unlikely to be challenged. The Court of Appeal therefore held that expert evidence should be limited to that which would have been available at the time of the underlying claim.

Phrased in that way, the approach is a logical one. While it may give rise to windfalls for claimants in certain situations, this is only because the evidence suggests that this is a windfall they would have recovered in any event but for their solicitor's breach of duty. It is important therefore for practitioners to understand the limits that the courts are currently prepared to place on permission to rely on expert evidence in lost chance litigation cases.

Liability

2018 saw the Supreme Court consider the issue of whether a solicitor owed a duty to a non client in Steel & Another v NRAM Ltd [2018] UKSC 13. In that case, the Supreme Court held that the solicitor acting for a borrower had not assumed responsibility to the mortgage lender on the facts of that case.

Duties to non clients were also considered in the conjoined appeals of Dreamvar v Mischon de Reya and P&P Property v Owen White & Catlin [2018] EWCA Civ 1082. In both cases, an imposter sold a property which it did not own and disappeared with the sale proceeds leaving the purchaser with neither its money nor its property. In Dreamvar, the buyer's solicitors had been found in breach of trust at first instance. In P&P the claimant's claim against the seller's solicitors and the estate agent failed at first instance. The claimants in both cases brought not only claims in tort, but also claims for breach of warranty of authority and breach of undertaking against solicitors for the seller. The claimants were successful in their claim for breach of undertaking against the solicitor for the imposter sellers on the basis that the undertakings given by the solicitors and the terms of the trusts on which they held the completion monies, required a transaction to be valid and so payment to an imposter put the solicitors in breach even without fault. The buyer's solicitor in Dreamvar was not granted relief under section 61 Trustee Act 1925 notwithstanding that it was not negligent. It follows that this decision places responsibility on solicitors for both parties in a fraudulent transaction. Read more here.

Another Court of Appeal decision which had a favourable outcome for the claimant was Stoffel & Co v Grondona [2018] EWCA Civ 2031 in which the Court of Appeal considered whether a client should be able to claim damages for professional negligence where the claim arose from a mortgage fraud. The Court of Appeal found in the claimant's favour because the public policy interest in clients being able to obtain civil remedies for the inadequate performance of professional services by solicitors outweighs the undesirable outcome of allowing claims to proceed where they arise from a fraudulent transaction. It is perhaps not so surprising based on its particular facts by reference to the principles laid down in Patel v Mirza. In the context of professional negligence claims, Grondona v Stoffel & Co clearly affirms that any illegality by the claimant must be directly linked to a breach of the retainer, or more closely connected to the terms of the retainer between the parties, to enable the illegality defence to operate. Read more here.

Aggregation

Having received guidance from the Supreme Court in AIG Europe Ltd v Woodman [2017] UKSC 18 on the interpretation of the aggregation provisions in the solicitors' minimum terms, which allow the aggregation of claims which arise from "a series of related matters or transactions", we have now seen the Australian Supreme Court of New South Wales applying this approach to one of the first reported post–Woodman aggregation decisions in the case of Bank of Queensland Ltd v AIG Australia Ltd [2018] NSWSC 1689.

The case is instructive as to the application of "related" in the context of aggregating "a series of related matters or transactions." The judgment demonstrates the need for precision around aggregation wording. Additionally, if policy wording allows parties to define "claim" by reference to group litigation order proceedings, then there may be no claims to aggregate at all. Read more here.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

The issue of causation in loss of chance cases continues to be a hot topic. In November 2018, the Supreme Court considered the Allied Maples loss of chance test on causation in lost litigation in Perry v Raleys. A decision is currently awaited.

The expansion of litigation funding and group litigation in professional negligence cases continues and we consider that this will be an ongoing trend in 2019. We considered the impact of how the courts are managing the costs in such cases at the end of last year.

Last year, we anticipated a large number of claims arising from soaring ground rents for leasehold properties. These claims have not materialised in great numbers in 2018. However, this may be about to change as there was a recent media report of one firm alone sending out 500 pre-action notification letters. Fraud and cyberattacks will remain risk areas, and the increasing use of Artificial Intelligence by law firms may also result in potential risk exposures.

The impact of the new Solicitors Regulation Authority rules requiring firms to publish details of their charges for members of the public and small businesses may be seen in 2019. This could lead to pressure on fees which may, in turn, impact client service and claims.

The Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal has recently consulted on whether the standard of proof in disciplinary proceedings should remain the criminal standard or change to the civil standard. The current standard of proof is considered too high by some and a change, if made, would reduce the threshold for finding a solicitor has breached the rules which may impact on claims.

Finally, at the time of writing, there is still a great deal of uncertainty about Brexit and where there are uncertainties, there may well be claims - if not in 2019 - in the future.

Surveyors and valuers

Since Grenfell, a great deal of investigation and assessment has been undertaken by various parties of not only residential blocks but also other public buildings such as hospitals and schools. Among those parties are PI insurers undertaking a review of their PI books to establish what exposure they have to property professionals (including surveyors) who have either installed or inspected cladding or other such materials that may pose a fire safety risk. Insurers are also asking at renewal for detailed information about work undertaken by installers and inspectors of cladding, and property professionals will need to ensure that they have collated this information in order to be able to renew on reasonable commercial terms.

Further, going forward, surveyors and other property professionals undertaking inspections or works involving cladding will want to consider very carefully the scope of the duty that they are undertaking and make sure that their clients understand the extent of their liability, preferably by suitable contract terms. Equally important is that property professionals keep up to date with any changes in regulations and professional practice which flow from the fallout after Grenfell.

Lender claims

In our review last year, we referred to the decision of the Supreme Court in the Tiuta case which concerned a lender wishing to refinance an earlier loan to the borrower and instructing a surveyor to provide a valuation of the property for that purpose. The Supreme Court held that the lender could only recover the new money advanced, not the existing loan, because the lender was already exposed to the loss on that loan whether or not the refinance transaction proceeded. We wondered then whether we would see cases where lenders had decided to change tack and seek damages from the valuer of the refinancing loan for the lost chance of being able to sue the valuer in respect of the first loan. Somewhat surprisingly, no such cases have been reported but this may just be a recognition of the fact that lender claims are now less common and the appetite for making new law on the part of potential lender claimants is limited.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

Whilst claims against surveyors remain relatively quiet, the Network Rail case may pave the way for more claims arising out of properties afflicted by JKW and other invasive species. Equally, property professionals who have either installed or inspected cladding or other such materials that may pose a fire safety risk may find themselves at risk of claims as this issue gains prominence and they should monitor this changing area to ensure that they give the correct advice and avoid claims in the future.

Tax and accountants

Scope of duty

One notable case in the early part of the year was Manchester Building Society v Grant Thornton UK LLP [2018] EWHC 963 (Comm). Accounting advice was given to a building society relating to lifetime mortgages where, until death, no payments were made. Accordingly, the building society decided to hedge the interest rates and sought advice from the defendant firm of accountants. The advice as to hedging was ultimately negligent with the result that the building society suffered significant losses.

Despite the losses being found to result from the negligent advice, the High Court ultimately held that those losses were not recoverable from the accountants on a number of grounds, principally that the firm had not assumed responsibility for the losses, it being (at paragraph 179):

"a striking conclusion to reach that an accountant who advises a client as to the manner in which its business activities may be treated in its accounts has assumed responsibility for the financial consequences of those business activities"

and, further, that:

" That circumstance illustrates, it seems to me, that the loss suffered by the Claimant, looked at broadly, sensibly and in the round, was not in truth something for which the Defendant assumed responsibility or the "very thing" to which the Defendant had advised the Claimant would not be exposed. Rather, the loss flowed from market forces for which the Defendant did not assume responsibility. Just as the Defendant had not assumed responsibility for the losses which would have been incurred had a counterparty exercised its right to terminate a swap, so the Defendant had not assumed responsibility for the very same losses which were incurred when the Claimant decided to close the swaps out, notwithstanding that that decision was taken because the advice given by the Defendant had been wrong."

As a result of all of the above, the accountants were found liable for a small part of the losses claimed and this case demonstrates the courts' continued willingness to take a fact sensitive approach to scope of duty arguments. This decision has been appealed and was listed to be heard on 15 January 2019.

In Iain Paul Barker v (1) Baxendale Walker Solicitors (A Firm) (2) Paul Michael Baxendale-Walker [2017] EWCA Civ 2056 the court, by a judgment dated 8 December 2017, construed section 28 Inheritance Tax Act 1984, which was of central importance to the structure of employee benefit trusts and to the likelihood of such trusts delivering purported tax advantages. A solicitor retained to give specialist tax advice had been negligent in recommending such a trust to his client without warning him of the specific and significant risk of HMRC construing the provision in a contrary way that would cause the trust to be fiscally ineffective. The court outlined general principles concerning the standard of care applicable where a solicitor's advice turned on his interpretation of legislation as follows:

"(i) The question of whether a solicitor is in breach of a duty to explain the risk that a court may come to a different interpretation from that which he advises is correct is highly fact sensitive...;

(ii) If the construction of the provision is clear, it is very likely that whatever the circumstances, the threshold of "significant risk" will not be met and it will not be necessary to caveat the advice given and explain the risks involved;

(iii) However, depending on the circumstances, it is perfectly possible to be correct about the construction of a provision or, at least, not negligent in that regard, but nevertheless to be under a duty to point out the risks involved and to have been negligent in not having done so…;

(iv) It is more likely that there will be a duty to point out the risks, or to put the matter another way, that a reasonably competent solicitor would not fail to point them out when advising, if litigation is already on foot or the point has already been taken, although this need not necessarily be the case…; and

(v) The issue is not one of percentages or whether opposing possible constructions are "finely balanced" but is more nuanced".

In short, this case is yet another warning to solicitors that they should be alive to the commercial implications of their advice. Permission to appeal has been refused.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

Levels of fines for misconduct continue to rise against the backdrop of increased regulatory pressures.

The Financial Reporting Council (FRC) (which is to be replaced, as to which see below) published its updated sanctions policy applicable to the Audit Enforcement Procedure which is effective from 1 June 2018.

The main alterations to the sanctions policy include (but are not limited to):

- a reduced discretion to apply a "discount" for cooperation. In order for cooperation "to be considered a mitigating factor at the point of determining appropriate sanction it will … be necessary … to have provided an exceptional level of cooperation."

- the inclusion of a list of examples of behaviour which could be considered an aggravating factor at the point of determining appropriate sanction, including "incomplete provision of documents, failure to provide adequate explanation of information provided and failure to comply with deadlines specified in Notices under the Audit Enforcement Procedure and other written requests.

- an explicit acknowledgment that greater emphasis is needed on the use of financial and non-financial penalties: "Decision Makers should also consider whether the sanction or combination of sanctions, financial and/or non-financial, achieve the objectives of the Audit Enforcement Procedure. There may be circumstances where the objectives can be achieved without a financial penalty."

As a consequence of the above guidance (albeit not binding on any decision maker) and the increased appetite for regulatory intervention, it is highly likely that we will see cases where significantly increased penalties are imposed.

Continuing with the theme of increased regulatory intervention, the Audit, Reporting and Governance Authority (ARGA) is to replace the FRC (previously branded "toothless and useless") with the government stating that it is to be "respected by those who depend on its work and where necessary feared by those whom it regulates." This follows Sir John Kingsman's review of the FRC in which, amongst other things, he called for greater transparency, an end to sector self-regulation, and a need for a fundamental overhaul of quality assurance tests for local authority audits.

The key points to be gleaned from the report are:

- Responsibility for oversight of actuaries should be transferred to the PRA

- ARGA is to take a pro-active approach, promoting both competition for statutory audit services and better quality audit and reporting standards, as well as regulating and registering the audit profession

- ARGA should have the power to take decisions on whether to launch audit investigations in cases where there is significant concern

- ARGA should have the same powers over accountants as it does over auditors, insofar as they deal with public interest entities

- Auditors should report to ARGA where they have concerns about the viability of a public interest entity (which duty currently only extends to banks and insurers); and

- ARGA should scrutinise auditor appointments to ensure that there is sufficient emphasis on quality and challenge.

The government is considering the recommendations made by Sir John but this will no doubt be a major shake-up in the world of audit, accountancy and business regulations.

Construction

No contract? No duty? No way!

In this year's round-up, the construction team examine recent decisions in which the courts have considered the scope of a professional's duty where there is no written contract, look at recent trends in adjudication and provide an overview of recent developments following the Grenfell tragedy and explore what it means for the construction industry in the months and years ahead.

This year has seen the continuing growth of cases where, before considering the professional's scope of duty, the courts have had to consider whether the professional had a contract with the claimant in the first place, and, if so, what the professional's contractual obligations were. The issue often comes to the fore if the professional wants to rely on a contractual liability cap or other contractual exclusions to limit their liability, which would otherwise be wider under general tortious principles. Consequently, the contract formation issue is often dealt with as a preliminary issue before the substantive issues of breach are addressed, and those preliminary issues can be (and often are) appealed up to higher courts, before going back to the original court for determination of the substantive issue.

While addressing the formation of contract issue as a preliminary issue can facilitate the early resolution of a claim, these sorts of preliminary issues can extend the duration and increase the costs of a case, as these issues have to be resolved before the substantive issues can be considered. There have been a number of recent cases which illustrate the delays which can occur.

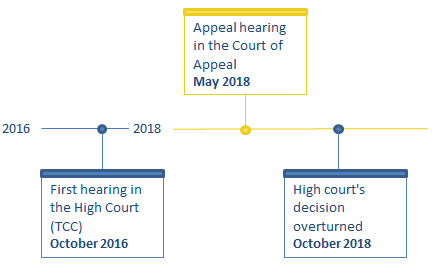

| In Arcadis v AMEC [2016] EWHC 2509 (TCC) and [2018] EWCA Civ 2222, the formation of contract hearing was heard in October 2016. That decision was appealed, and two years later the substantive issues are yet to be heard. |  |

|

|

Burgess & Anr v Lejonvarn [2016] EWHC 40 (TCC), [2017] EWCA Civ 254, [2018] EWHC 3166 (TCC) was a £265,000 claim in which the contract formation issue was dealt with as a preliminary issue. It took 3.5 years in court (excluding pre-action stages) to resolve | |

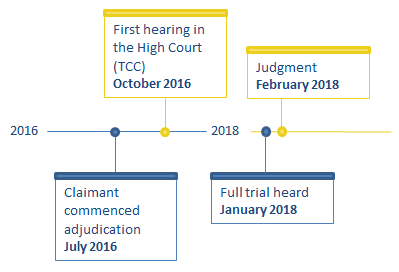

| In Dacy Building Services v IDM Properties [2018] EWHC 178 (TCC) the contract/no contract issue was first raised in an adjudication which was commenced in July 2016, but judgment was not formally handed down on that point until in February 2018. |  |

Emerging themes from recent cases

We will now take a closer look at recent contract/no contract cases and explore some of the themes to emerge as follows:

- Where there is a written contract;

- Where there is an oral contract;

- Where is no contract but there is a duty of care in tort; and

- Where there no contract and no duty.

Written contract

Arcadis v AMEC [2018] EWCA Civ 2222

AMEC was a specialist concrete sub-contractor who appointed Arcadis to carry out design works on two projects, in anticipation of a wider agreement being entered between the parties governing all of Arcadis' work. Arcadis carried out the works for the two projects on the basis of a letter of intent but the wider agreement never materialised, it appears partly because of the robust approach each party took to the negotiations which lead to a breakdown of the relationship.

AMEC alleged that Arcadis' designs on one of the two projects were negligent, resulting in the need to demolish and re-build the development in question.

AMEC claimed £40million from Arcadis whose main defence was that it was not liable for the defects but argued in the alternative that there was a contractual cap on liability of £610,515. AMEC argued there was no contract in place and therefore no cap.

At first instance, the Court came to a half-way house holding that there was a contract in the form of the letter of intent and that "in circumstances where works have been carried out, it will usually be implausible to argue that there was no contract." However, the Judge then went on to decide what the terms of that contract were and he determined that while the parties had clearly discussed a cap on liability, no contract which included the cap on liability asserted by Arcadis or indeed any cap had ever been finalised. Arcadis' liability was therefore unlimited.

On appeal, the Court of Appeal agreed there was a contract but disagreed as to the terms of that contract. On the facts, it held that a cap was incorporated by virtue of a cap being included in the existing terms under which Arcadis was working on another project, and that cap was £610,515. That would therefore have been a relief for Arcadis (and its insurers). However, AMEC, who it appears had already settled the claim from the main contractor (Kier) in the "tens of millions", will be left with a serious shortfall.

Oral contract

Dacy Building Services v IDM Properties [2018] EWCH 178 (TCC)

This case relates to payment obligations and therefore would likely be excluded from any professional indemnity policy. However, the case raises interesting questions about the scope of professionals' roles on projects and how they can find themselves taking on liabilities they do not expect. When this happens alongside professional negligence allegations, especially when it is not clear if there is a contract in place, the issues often become intertwined and in depth reviews have to be carried out to establish what exactly is covered by the insurance policy in question.

The background to the case is that HOC (UK) Limited (HOC) was the main contractor for works on a project in Camberwell, London. The employer was O'Loughlin Leisure (Jersey) Ltd (O'Loughlin).

IDM Properties (IDM) were also involved providing project management services and were the contract administrator under the main contract. However, during the course of the project, it appears that IDM took on a different and more wide ranging role. In particular, when HOC encountered financial difficulties, HOC suggested bringing in another contractor, Dacy Building Services Ltd (Dacy) to assist HOC with completing its works. However, Dacy had previously had problems obtaining payment from HOC and therefore refused to contract with HOC, insisting they would contract only with a different party. For some reason, which is not clear from the case, this was not the employer, O'Loughlin, but instead was IDM.

Dacy then proceeded to carry out its services. Payment to Dacy was administered through HOC but was ultimately paid by IDM. HOC would approve Dacy's payment applications and pass them to IDM to be certified and paid. Following three successful payment applications, IDM did not pay the fourth and fifth applications and Dacy claimed an undisputed sum of £247,250 plus interest from IDM.

There was no written contract between IDM and Dacy and therefore IDM argued they were not liable for Dacy's unpaid invoices. IDM argued that, if there was any contract, it was between Dacy and HOC on a standard sub-contracting basis.

The Court disagreed and decided that, based on the contemporaneous documentation and events, there clearly was an oral contract between Dacy and IDM and there was no contract between Dacy and HOC, given Dacy had made their intention not to contract with HOC very clear.

This left IDM liable to Dacy for the disputed sum. It is not clear why IDM were funding the project, considering they were providing project management services only, and were not the employer. It may be that in fact behind the scenes the employer was providing funds to IDM to pay Dacy and the employer then stopped funding IDM such that, due to the vague contractual position, IDM found itself liable to Dacy for sums which it was not recovering from the employer.

No contract, but duty of care in tort

Burgess & Another v Lejonvarn [2018] EWHC 3166 (TCC)

Our third case example illustrates the pitfalls of professionals providing informal assistance to friends but equally highlights the potential liability to which professionals may be exposed when offering ad hoc advice as a favour to clients.

Mr and Mrs Burgess owned a house in London, where they wanted to carry out extensive gardening/landscaping works. An architect friend of the Burgesses', Ms Lejonvarn, agreed to provide them with free architectural services.

However, the relationship between the parties broke down, with the Burgesses ultimately appointing another architect to finish the project. The Burgesses claimed that Ms Lejonvarn had carried out her services negligently, leading them to suffer losses of £265,000.

Ms Lejonvarn's defence on the preliminary issues was that there was no contract between her and the Burgesses and/or that she did not owe them a duty of care in tort; therefore, there was no question of negligence to be decided.

The High Court and Court of Appeal both agreed that there was no contract between the parties but that Ms Lejonvarn did owe the Burgesses a duty of care in tort, and that included a duty to prevent pure economic loss.

On the facts however, when the case went back to the High Court, the Court held that Ms Lejonvarn had not breached that duty of care. That is partly because the duty she owed in tort was limited to using reasonable skill and care in the services she provided; there was no obligation on Ms Lejonvarn to carry out services. In other words, there was no obligation on her to do design work but the design work which she did do had to be done with reasonable skill and care. This meant that the duties on Ms Lejonvarn were significantly different from those she may well have been under had there been a contract in place.

The Court held that, on the facts of the case, Ms Lejonvarn had not been negligent. This is therefore an example of where it was in fact preferable for the professional that it was found there was no contract in place because that limited the duties and liabilities of the professional.

No contract and no duty

BDW Trading Ltd v Integral Geotechnique (Wales) Ltd [2018] EWHC 1915 (TCC)

Our final case is a further example of In June 2012, where it was in fact of benefit to the professional that it did not have a contract in place.

Barratt Homes and David Wilson Homes (BDW), received a tender package from a local council for a site that they intended to buy from the council. This tender package included a site geotechnical package prepared by Integral Geotechnique (Wales) Limited (IGL).

When originally instructing IGL to produce the geotechnical package, the local council had requested that the package be capable of assignment with warranties to the eventual site purchaser. However, no assignments or warranties were in fact put in place.

BDW subsequently bought the site, relying in part upon IGL's geotechnical report. However, BDW then discovered asbestos on site which IGL's report had not identified, and BDW incurred significant extra costs in removing the asbestos. BDW sought to recover those costs from IGL.

As there was no contract, and no warranties, between BDW and IGL, BDW pursued a claim in tort against IGL for failure to identify the site's asbestos problem. However, the Court held that IGL had not assumed a duty of care towards BDW. There were a number of factual reasons for this, including the lack of proximity of relationship between the parties, IGL's appointment expressly excluding third party rights and BDW failing to secure assignment of the council's rights in relation to the package which BDW did have a contractual right to pursue.

The question of the professional's negligence in producing the report never became relevant which in fact meant this claim was probably disposed of more quickly, and cheaply, than if the substantive issues had to be considered in detail. The contract that it did have, with the Council, was also robustly drafted to exclude third party claims.

Summary

In summary, the above cases all illustrate how issues regarding contract formation can often become more important than the more thorny and subjective issues of negligence.

If a claim can be defended on the basis there is no contract (or indeed that there is a contract, and therefore contractual caps and limitations apply), then that can resolve a case more quickly and cost effectively than by obtaining costly expert evidence and engaging in lengthy trials. On the other hand, these sorts of preliminary issues can extend the duration and increase the costs of a case, as they have to be resolved before the substantive issues can be considered.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

In an ideal world, professionals would ensure all their appointments are clear, in writing and robust. In reality, due to the nature of the construction industry, that is often commercially not possible and professionals are forced into situations where the contractual position may not be clear. We are therefore likely to continue to see litigious activity in relation to these areas as time goes on.

Recent trends in adjudication

There have been a few recent trends which have changed the way parties have used adjudication to resolve disputes, which we explain below.

Smash and grab

In recent years there has been the rise of the so called 'smash and grab' adjudications. These were of particular concern to professional quantity surveyors / project managers who may have inadvertently missed the timing for service of a payment / pay less notice on behalf of an employer as part of the interim monthly payment application process. If a contractor had made an application for payment of, say, £1m, and no payment / pay less notice had been issued on behalf of an employer, then court decisions had said that the employer was deemed to have agreed to the sum due (e.g. the £1m claimed by the contractor). A line of authorities commencing with ISG v Seevic [2014] EHWC 4007 had held that an employer was unable to commence a separate adjudication for the true value of the same application, where a first adjudication had determined that a contractor was entitled to payment of its application due to the failure to serve the requisite notices.

However, in November 2018, the Court of Appeal in S&T (UK) Limited v Grove Developments Limited [2018] EWCA Civ 2448 held that an employer, who has failed to serve both a payment notice and a pay less notice, is nevertheless entitled to commence an adjudication to have the true value of the application assessed and to reclaim any sum which has been overpaid (albeit the employer must first pay the sum due as a result of failing to serve a notice). As such, this is good news for professional surveyors / project managers, as the decision has somewhat removed the wind from the sails of 'smash and grab' adjudications. Whilst a contractor may still take a punt at receiving an interim cash windfall, we expect that we are now passed the peak of 'smash and grab'. Read more here.

Throwing in the kitchen sink

Adjudication was originally envisaged as a speedy process to resolve cash flow during the course of construction projects. As those in the industry have become increasingly familiar with adjudication, disgruntled parties have used the adjudication process on a wide number of disputes notwithstanding that some would argue that adjudication wasn't meant for particularly complex disputes or those involving a significant amount of documentation.

As cash pressures increase in the construction industry, we are seeing a trend in the use of adjudication not only for professional negligence claims but also for very substantial final account claims. These are sometimes referred to as 'kitchen sink' adjudications because everything is 'thrown in'. In those cases, referral documentation can comprise hundreds of folders of material resulting in an adjudication timetable of several months (as opposed to the original 28 days envisaged by the Construction Act) and can take the form of 'mini trials', with the exchange of witness statements, expert reports, an attendance at a meeting (or several) which could involve cross-examination and numerous submissions. The advantage to the referring party is that, whilst the timetable is longer than a 'typical' adjudication, the process is still much quicker than embarking on a TCC trial.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

We expect to see adjudication continuing to gain popularity as a means of dispute resolution in the construction industry and the adjudication process adapting to accommodate much larger value, more complex disputes.

Grenfell's continued fallout: rethinking construction risk

The Grenfell Tower tragedy on 14 June 2017 continues to loom large in the UK's collective consciousness. The Government swiftly announced a public inquiry into the causes of the fire, and terms of reference were set on 15 August 2017. Since then, the Inquiry has heard compelling evidence about the personal impact of the tragedy on the residents of Grenfell Tower, and from the individuals who were involved in the rescue operations. The Inquiry has also released over 18,000 pages of material and numerous expert reports.

The construction industry has been paying close attention to the final report prepared by Dame Judith Hackitt, published on 17 May 2018. The Report concludes that the current building safety regulatory framework, including the regulations which apply to the specification and testing of construction products, is "not fit for purpose". In June 2018, in response to public pressure and the Hackitt Report, the Government announced its intention to "ban the use of combustible materials on the external walls of high-rise residential buildings, subject to consultation”. The consultation took place, and the long-awaited ban on combustibles was finally announced on 29 November 2018 and came into effect on 21 December 2018. We consider below how the construction industry must now change its approach to cladding (and other combustible materials) going forward, and how potential issues on existing buildings should be addressed.

The ban on combustibles in new projects

Previously, it was possible for buildings over 18m to satisfy Building Regulations requirement for resisting fire spread over the external walls by using materials of "limited combustibility" or for testing to be undertaken to establish compliance with the requirements of Approved Document B. The ban now removes the discretion for duty holders to use either of these approaches to demonstrate compliance.

Key points are as follows:

- The ban applies to all new residential buildings above 18m in height, as well as new dormitories in boarding schools, student accommodation, registered care homes and hospitals over 18m

- The ban also applies where building work (as defined in in the Building Regulations) is being undertaken, including changes of use and material alterations

- There are some exemptions for components where non-combustible alternatives are currently not available

- The ban is not retrospective.

Identifying cladding risks in existing projects

The Government says it is committed to supporting local authorities to compel owners of privately owned buildings to remediate unsafe cladding. The Government says there are current plans in place for 98 private sector high rise buildings to have remedial works carried out, but those numbers are expected to increase.

The Government has now released "operating guidance" to aid in the assessment of high-rise residential buildings with unsafe cladding. Insurers will be particularly interested in the treatment of different categories of ACM cladding. Category 3 cladding (ACM cladding with polyethylene filler) is now deemed unsafe, with the Government advice stating:

" The expert panel does not believe that any wall system containing an ACM category 3 cladding panel, even when combined with limited combustibility insulation material, would meet current Building Regulations guidance, and it is not aware of any tests of such combinations meeting the standard set by BR135. Wall systems with these materials therefore present a significant fire hazard on buildings over 18m."

Other less combustible types of cladding might pass the testing requirements if used in conjunction with sufficiently robust fire mitigation measures.

Government response

On 18 December 2018, the Government published 'Building a safer future - an implementation plan', its long awaited formal response to the recommendations set out in the Hackitt Report. The general response is that the Government agrees in principle with the majority of the recommendations put forward by Dame Hackitt and will consult on the specific details in Spring 2019. Please click here to read more.

We are continuing to monitor developments closely, so please watch this space for further developments.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

Grenfell - cladding

The Grenfell tragedy is already understood to have created some very significant exposures for the construction industry and the construction professional indemnity insurance market, and there continues to be uncertainty about the full extent of the potential fall-out. What has become clear is that cladding-related issues are already affecting the availability of professional indemnity insurance for professionals who have any involvement in the design, specification or management of projects which involve cladding materials, and the terms on which underwriters are prepared to offer or renew cover.

Remedial works are already underway in relation to a number of large projects which have used Grenfell-style cladding schemes but there are known to be many more buildings and projects about which complaints or concerns have been raised by owners or residents where no concluded agreement as to what remedial works are necessary or who should bear the cost has been reached. Many in the construction industry feel that potential claims are lying dormant pending further regulatory developments or news of funding proposals from the Government, local authorities or the NHBC, which is contributing to ongoing uncertainty for the construction industry and their insurers.

The Government appears to be intent on pushing for all necessary remedial works to be undertaken as soon as possible, and has indicated its intention to support local authorities to undertake enforcement action where necessary. Where remedial works have stalled due to disagreement between the building owner or employer and the project team as to who should bear the cost of the works, or disagreements about the scope or cost of the proposed remedial scheme, we can now expect to see some activity.

The release of the Government's latest guidance should bring some certainty to the cladding testing process, but it could also cause dormant claims to escalate and prompt some new notifications to insurers.

On the legal side, we are yet to see any significant legal decisions to emerge out of the Grenfell tragedy which change the landscape around the tortious or regulatory liability of construction professionals. However, unusual situations can often create new law. There is a lot at stake for many parties involved in the Grenfell tragedy. This could mean that parties who have a particular interest in pursuing legal redress (such as a claimant advocacy group) or find themselves facing a significant exposure (such as defendant who wishes to bring contribution claims against other members of the project team) may be prepared to mount legal challenges which test the boundaries of existing principles of contractual and tortious liability. The types of legal issues which could be tested post-Grenfell include:

- What comfort can a project team get from the fact that a project satisfied the requirements of Building Control? The failure to comply with Building Control would ordinarily regarded as prima facie negligence, but what about the converse?

- What about the risk of hindsight claims? A party's negligence should be assessed against the facts and risks which were known at the time, not with the benefit of hindsight. However, with a tragedy as catastrophic and visible as Grenfell, it could be difficult for experts and the Courts who are assessing the resultant claims to escape the lens of hindsight.

- When will a member of a project team come under a tortious duty to warn? Can a member of the project team escape liability by doing what it is (strictly) contracted to do, and no more? Or could there be circumstances in which the project team is under a wider collective duty to collaborate to ensure the safety of a project?

It remains to be seen how the case law will develop, but the legal issues which have emerged as a result of the tragedy will almost certainly be tested in the years to come.

Grenfell – non-cladding developments

Most of the commentary about the Hackitt report has focused on ensuring the safety of materials used in construction (particularly cladding), but it is worth noting that of the 53 recommendations in the Report, only seven of them relate to construction materials.

Of particular interest for professional indemnity insurers is the Report's recommendation to extend the statutory obligation to ensure building safety to certain construction professionals and contractors. The Construction (Design and Management) Regulations (known as the "CDM Regulations") already create a statutory framework which aims to ensure that health and safety issues are properly considered during a project's development. The Report recommends that the role of construction professionals and contractors be extended to include CDM-style building safety responsibilities to ensure the building safety standard of the final product. The Government has already confirmed its agreement in principle to this recommendation with a full consultation expected in the Spring. If the Government implements this recommendation in full, it could mean, in practice, that an architect who is designing a multi-occupancy high risk residential building of 10 storesy or more will not only have to comply with its duties in contract and tort, but will also be subject to a statutory obligation to consider, during the design phase, how the project can achieve building safety. This would create a significant additional avenue of exposure which professional indemnity insurers will need to address.

For our thoughts on what is on the horizon in 2019 for construction and engineering more generally please see our article: A year of developments in construction, and what 2019 may hold.

Pensions

This year has seen a number of significant developments.

GDPR

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) finally came into force on 25 May 2018 and with it introduced both new duties and significantly higher fines for non-compliance. Although trustees will not have to register with the ICO as "data controllers", those duties include requiring trustees to ensure that their contracts with the service providers are GDPR compliant, and that they have adequate cyber security and data protection policies in place.

Auto-enrolment/GMP equalisation

This year also saw the introduction of government proposals regarding auto-enrolment (reducing the auto-enrolling age limit to 18 as well as removing the lower limit on earnings on which contributions must be paid).

A case with auto-enrolment implications was the High Court decision in Lloyds Banking Group Pensions Trustees Limited v Lloyds Bank PLC [2018] EWHC 2839 (Ch) which concerned the employer's duty to equalise Guaranteed Minimum Pensions (GMPs) for men and women. In an eagerly anticipated decision the court held that a trustee is under a duty to amend schemes in order to equalise benefits for both men and women, that there are a number of methods of equalising for GMPs and that trustees are obliged to make back payments (plus interest) to scheme members. Now the decision is known, all schemes with GMPs will need to consider what steps to take regarding equalisation in respect of GMPs.

Validity of amendments to pensions

The Court of Appeal handed down its decision in British Airways Plc v Airways Pension Scheme Trustee Ltd [2018] EWCA 1533 on whether trustees were permitted under the power of amendment in the scheme to introduce discretionary pension increases. BA's pension scheme was such that any increases were calculated by reference to annual pension increase review orders issued by the government which in turn were linked to the RPI. The government subsequently switched from RPI to CPI and the trustees of the scheme unilaterally amended the scheme to introduce a new trustee power to allow discretionary increases subject to certain restrictions. The High Court held that the trustees' decision to amend the rules to allow the discretionary increase was allowed as a valid exercise of the scheme’s power of amendment and was not beyond the scope of what the power allowed.

On appeal, the court found in favour of BA with the consequence that the trustee's decision to exercise its unilateral power of amendment to introduce a new trustee power to provide discretionary pension increases was held to be invalid. In short:" … the function of the trustees is to manage and administer the scheme; not to design it. The general power that is given to them is limited to a power to do all acts which are either incidental or conducive to that management and administration.”

The case clarifies the law for other schemes with rules that make express reference to RPI, but contemplate the possibility that a different index could be used. The take away point from this case is that if trustees are unsure of the nature and extent of their powers and duties under and in relation to a scheme then legal advice ought to be obtained.

In the meantime the saga looks set to continue with permission to appeal to the Supreme Court having been given. Watch this space.

In the Supreme Court case of Barnardo's v Buckinghamshire & Ors [2018] UKSC 55, the court dealt with the thorny issue of the appropriate index to be used for pension increases. The statutory minimum basis for pension increases changed from RPI to CPI from 1 January 2011 but the impact on any given scheme very much depends on the way in which the scheme rules are drafted. In Barnardo's, RPI was defined as "the General Index of Retail Prices published by the Department of Employment or any replacement adopted by the Trustees without prejudicing Approval", and so, the question to be determined was whether a trustee can choose to adopt CPI as a replacement.

The Supreme Court held that trustees have no discretion to change the index and that the appropriate interpretation was that an alternative index could only be used where RPI ceased to be published.

Trustees would be wise to revisit their own documentation to ensure that they have correctly interpreted the relevant provisions to ensure that their scheme is not materially impacted.

Master trust authorisation regime

Finally, from 1 October 2018 a new master trust authorisation regime came into force, requiring a master trust (an occupational pension scheme that provides money purchase benefits, is used or intended to be used by two or more employers, is not used or intended to be used only by employers which are connected with each other and is not a public service pension scheme) to be authorised by the Pensions Regulator. Existing master trust schemes have only 6 months to apply for authorisation and will need to demonstrate that the scheme meets the required standards across a number of criteria, including (but not limited to) demonstrating that the scheme is fit and proper, that IT systems enable the scheme to run properly and that there is a plan in place to protect members if something happens that may threaten the existence of the scheme.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

Separately (and following on from the above point), to combat "pensions liberation," the government is planning to legislate to restrict a pension scheme member's statutory right to transfer benefits so that the right will only apply to a personal pension scheme, master trust, or occupational scheme to which a member can show a genuine employment link. Implementation of these amendments to the statutory transfers regime will be delayed until the master trust authorisation regime has been introduced so the new measures are not anticipated to be in place until 2019 but it is hoped that as a result they will help to prevent pension scams (usually involving a transfer of an occupational pension scheme) and dealing with the issues which arose in cases such as Donna Marie Hughes v Royal London Mutual Insurance Society Ltd [2016] EWHC 319 (Ch).

Finally, another interesting case to watch is the longstanding row between the government and a number of judges following the Employment Appeal Tribunal's decision to reject the government's challenge to an earlier decision that its transitional pension provisions for judges amounted to unlawful age discrimination. The case has now been heard by the Court of Appeal which upheld the Tribunal's decision but it remains to be seen whether the government will appeal: ( 1) Lord Chancellor & Secretary of State for Justice (2) Ministry of Justice v (1) McCloud & Others (2) N Mostyn & Others: Secretary of State for the Home Department, Welsh Ministers & Others v R Sargeant & Others [2018] EWCA Civ 2844. Read more here.

Insurance brokers

Scope of duty

Insurance brokers have had somewhat of a tough time of it in recent years. There appears to be a general trend towards imposing a wide-ranging scope of duty of care on brokers in reported decisions, and the introduction of the Insurance Act 2015 arguably added to the burden.

Brokers are faced with the task of giving their clients sufficient information and warning about their duties of disclosure to insurers, and, importantly, the consequences of non-disclosure, yet at the same time clients will often say that the broker had given too much information/documentation so they did not consider it in any detail! This is a very tricky line to tread. For a review of broker's duties click here.

The recent decision in Avondale v Arthur J Gallagher [2018] EWHC 1311 (QB) confirms the approaches taken in previous cases: the adequacy of a broker's communication to its client as to what is material ought to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. The judge in that case noted the lack of expert evidence adduced by Avondale to support its breach of duty allegations and ultimately found against Avondale, apparently in large part because of this. We therefore expect that obtaining expert evidence supporting the broker's defence on breach will become common practice.

Causation

As in all negligence cases, causation as well as breach must be proved. In relation to brokers, a key factor is whether there are other reasons why the underlying insurer would have avoided cover (for which the broker is not responsible). If so, causation will not be established. This may seem obvious but it is difficult to apply in practice for two reasons:

First: what is the principle behind the question of causation?

The court in Pakeezah Meat Supplies Ltd v Total Insurance Solutions Ltd [2018] EWHC 1141 (Comm) reduced damages payable to the claimant by 25% to take into account the possibility that an insurer in the market might not have insured the claimant at all because of the size of its oil fryers. This feels very much like a 'loss of chance' deduction, but needs to be contrasted with the decision inDalamd Limited v Butterworth Spengler Ltd [2018] EWHC 2558 (Comm) where the court found that the issue of what indemnity would have been available to the claimant but for the broker's breach, should be determined on the basis of balance of probabilities (giving a binary outcome) rather than using 'lost opportunity' principles.

The principle seems to be that where the question is about what the claimant, broker or underlying insurer would have done during the underlying coverage dispute, then the court must decide how the underlying insurance would have applied on the balance of probabilities, as if the underlying coverage dispute had gone to trial. However, when the question is a wider one about whether there would have been cover available in the market generally, then loss of chance principles come into play.

Secondly: how does one gather evidence on these issues?

Unless the underlying insurer is still part of the litigation, or has written an extremely comprehensive repudiation letter, the broker is left to try and secure evidence from the underlying underwriter and/or claims manager at the insurer for witness evidence. However, it is difficult to imagine a situation in which the insurer is going to be overly pleased to provide such evidence (due to time, cost and potential reputational damage) and our experience is that unless the insurer is a party to the litigation, the individuals concerned are unlikely to be forthcoming.

It is easy for a judge to say that evidence of underwriters would be admissible and could be adduced – by either the broker or the claimant (indeed, this is what the judge said in Dalamd). In practice, however, if the underwriter does not want to co-operate in giving a witness statement, then the court will be left to determine how the underlying policy would have responded on the balance of probabilities. Rather a gamble on both sides….

Impact of the Insurance Act 2015

Many brokers' cases being decided at the moment are still under the 'old' law (eg Dalamd and Pakeezah Meat related to fires in 2012 and 2013 respectively and insurance policies in force at that time). The new suite of insurer remedies arising under the Insurance Act 2015 (which came into force in August 2016), are not as draconian in all cases as outright avoidance of the policy for a non-disclosure. The 'new remedies' will make it important to have an understanding of the insurer's position to be able to ascertain whether or not the insurer would have insured, and on what terms – and the knock on effect on the claim against the broker. It may also be necessary to have expert evidence on causation issues, for example, if there is an argument that the claimant was uninsurable in the market.

Take away points

- Decisions really are very fact specific. There are no hard and fast rules and the judge will look at each claim on a case by case basis

- It is highly likely now that in all but the most obvious cases, claimants will require expert evidence to support their allegations of breach with the knock on effect that the broker will want their own expert too

- Ascertaining the correct causal approach to determining how the underlying policy would have responded but for the broker's alleged breach is key. And often overlooked by claimants

- Key liability issues will depend on the judge's view on the day, which is extremely difficult to judge in advance. There may also be practical difficulties in gathering the evidence to support the broker's defence (ie underwriter witnesses of fact) so early consideration should be given to securing this evidence.

What is on the horizon for 2019?

The failure of a number of insurance companies in recent years prompted the FCA to publish guidelines in August 2018 on the due diligence it expects brokers to carry out on the insurance companies it uses when placing insurance. Failure to comply with these guidelines to the letter could expose brokers to a claim in the event that an insurer goes out of business leaving policy holders uninsured.

On a similar note, the Insurance Brokers' Good Practice Guide, a voluntary code of conduct launched in 2017 by BIBA following consultation with interested parties, will be a useful resource for brokers but also a benchmark for acceptable conduct. Insurance brokers should ensure that they monitor this guide as well as FCA guidelines in order to ensure that they act consistently with good practice and avoid claims in the future.

Finally, insurance brokers will become subject to the Senior Managers Certification Regime from December 2019. This means that senior managers will be personally accountable for wrongdoing occurring in areas of business for which they are responsible. Other employees may be subject to the certification regime and conduct regime. Again insurance brokers must ensure that they are aware of their obligations under the regime.

IFAs

It has been something of a mixed bag as far as case law in relation to claims against IFAs is concerned for 2018. We highlight some interesting developments below.

Transfers into SIPPs

Alistair Rae Burns v FCA [2018] UKUT 246 (TCC)

In a decision to alarm any IFA advising on the merits of transferring the value of occupational pension and personal pension benefits into SIPPs, the Upper Tribunal Tax and Chancery Chamber found that the FCA's imposition of a substantial financial penalty and a prohibition order on a regulated financial adviser was reasonable.

Mr Burns was approved by the FCA as a CF1 (Director) of Tailormade Independent Ltd (TMI) which specialised in advising retail customers in relation to the transfer of the value of their pensions into SIPPs. TMI was one of a number of businesses operating under the Tailormade brand and Mr Burns had an interest in each business. As well as TMI, which was authorised as an IFA, the Tailormade group included an unregulated company, Tailormade Alternative Investments Ltd (TMAI) which promoted alternative investments to customers. Its advice model was that TMAI would not advise on the merits of customers acquiring the alternative investments and TMI would only advise on the merits of the customer transferring his pension to a SIPP. TMI did not advise on whether such investments were suitable for the customer, proceeding on the basis that the SIPP was a self-invested product where the customer independently chose to acquire investments and was advised to seek his own advice on the merits if he thought it necessary.

The FCA held that the relevant business and advice models were flawed in that these failed to ensure that customers were treated fairly and given appropriate advice on transfers of the value of existing pension arrangements to SIPPs which in turn invested in alternative investments promoted by TMAI. In addition, the director, Mr Burns, was receiving financial benefits when the pension monies were transferred so that there was a direct conflict of interest between Mr Burns and the company's customers which was not disclosed. The FCA imposed a significant financial penalty on the firm of £233,600 and a prohibition order on Mr Burns. Mr Burns referred the decision to the Tribunal.

The Tribunal found that the rights of a SIPP beneficiary under the Trust arrangements that established a SIPP constitute a specified investment in accordance with article 82(2) of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (Regulated Activities Order) 2001. Accordingly, as a specified investment, the rights of a beneficiary under a SIPP were subject to regulation by the FCA.

The Tribunal found that firms advising a client on the merits of establishing a SIPP with a SIPP provider is carrying on a regulated activity which will be subject to the relevant FCA Principles and Conduct of Business Rules (COBS). The Tribunal also held that where a firm advised on the merits of establishing a SIPP in circumstances where it knew that the SIPP would invest in assets which were not specified investments, then advice on the merits of the underlying investments should form part of the regulated advice on the merits of establishing the SIPP.

The Tribunal examined COBS 9.2 which obliges firms to assess the suitability of its recommendations. COBS 9.2.1 provides that a firm must take reasonable steps to ensure that a recommendation is suitable for its client and, when making a recommendation, the firm must obtain necessary information regarding the client's knowledge and experience in the relevant investment field, financial situation and investment objectives. The Tribunal held that this obligation requires a firm which makes a recommendation to establish a SIPP to consider if the SIPP is a suitable vehicle for the customer in light of their personal circumstances and in light of the investments which it is proposed will be held within the SIPP. The recommendation must be made based on the customer's knowledge and experience as relevant to the type of service concerned, his financial situation and investment objectives. Accordingly, the IFA must also assess whether the underlying investments to be held within the SIPP match the customer's attitude to risk as well as his knowledge and experience. If the investments do not match the customer's attitude to risk, the SIPP should not be recommended.

The Tribunal acknowledged that one of the features of a SIPP is that customers can select the investments made by the SIPP. In such cases, the obligations of the IFA firm under COBS 9.2 might be more limited. The Tribunal pointed out that the firm would have to consider whether the investments were consistent with the customer's attitude to risk and whether the customer had the experience and knowledge to understand the risks involved. If so, the IFA firm could reasonably take the view that the recommendation to establish the SIPP with a view to the client making the relevant investments through the SIPP was suitable. If not, the firm would have to advise the customer of its views and provide appropriate warnings but, of course, the customer could still decide to proceed notwithstanding that advice and those warnings.

The Tribunal found that in all cases, the investments promoted by TMAI were incompatible with the customers' attitude to risk and TMI could not have been satisfied that the customers had the necessary experience and knowledge to understand the risks involved with the proposed investments. In the circumstances, the business model was flawed and TMI's personal recommendation process did not comply with the FCA's regulatory requirements.

The Tribunal found that Mr Burns was personally culpable with regard to the flawed business model and had failed to ensure TMI's business model was compliant with its regulatory obligations. The conflict of interest arising from the business model concerned the director personally and was one which any reasonably competent director should have identified. In the circumstances, a reduced financial penalty and the prohibition were upheld.

IFAs need to check business models carefully where different companies (including unregulated companies) in a group work together to deliver services. Directors should also bear in mind the risk of the potential for conflicts of interest where interests in different businesses may overlap. More generally IFAs need to be alive to the need to consider the investments to be held within a new SIPP and not just the suitability of the SIPP holding them.

Accrual of the cause of action and date of knowledge for limitation

Graham Davey v 01000654 Limited (formerly Heather Moore & Edgcomb Ltd) [2018] EWHC 353 (QB)

This case addressed several issues, the main issues of interest to IFAs being the date on which the primary six year limitation period accrued when deficient financial advice was given for the purposes of section 2 and the date a client acquired knowledge for the purposes of section 14A of the Limitation Act 1980.

Section 14A of the Limitation Act extends a claimant's time to bring court proceedings by three years from the date on which the claimant acquired both the knowledge required for bringing an action for damages in respect of the relevant damage and a right to bring such an action.

Mr Davey was advised by the defendant IFA to transfer the value of his BA pension occupational pension into a personal pension with Skandia Life and alleged he had suffered loss as a result. The case turned on its facts but the court held that, in the context of negligence claims against IFAs arising out of failed or poorly performing investments, the usual case is that damage is suffered on the making of the bad investment. Thus the cause of action arises when the investment has been made even if the true measure of loss is not apparent or quantifiable until a later date.

The court distinguished between no transaction and a flawed transaction for limitation purposes. A no transaction case might involve loss which only arises on the happening of a later event in relation to which the transaction creates a contingent loss. The loss is prospective and might not arise but when it does, it is attributable to the negligence which caused the claimant later to become exposed to it. A flawed transaction case, however, involves a transaction with inherent flaws the moment it is entered into. The loss may never arise, but if it does it is referable to risks present from inception.

The court found that Mr Davey's claim was a flawed transaction case where the cause of action arose on the making of the bad investment, i.e. the transfer from the BA scheme. It reached this view based on the fact that an alternative preferable arrangement existed in the form of Mr Davy's membership of the BA scheme which was given up when the transfer to the personal pension proceeded, as opposed to a no transaction case where a claimant's position became worse only on a contingency, albeit one which would not have arisen but for the IFA's negligence.

As a matter of fact, the court found that Mr Davey had been aware from August 2006 that the investment he had made was risky as a result of the heavy equity based nature of the funds in which his personal pension had invested which had resulted in a significant loss of capital. In such circumstances, the court found that Mr Davey had acquired the necessary section 14A knowledge to enable him to bring a claim against his former IFA more than three years prior to a limitation standstill agreement entered into in in 2014. Therefore his claim was time barred before the standstill took effect.

Claimants frequently try to bring "stale" claims against IFAs and equally frequently try to rely on section 14A to bring the claim within the statutory time limits. Graham Davey makes it clear that those defending such claims must look at the nature of the transaction and the claimant's date of knowledge very carefully.

SIPP administrators: scope of duty

Berkeley Burke SIPP Administrators Limited v The Financial Ombudsman Service and Wayne Charlton and FCA [2018] EWHC 2878 (Admin)

In a worrying development for SIPP administrators, the court held in the case of Berkeley Burke that SIPP administrators, while not retained to advise, were still obliged to consider if proposed investments under SIPPs were viable and should be accepted into the SIPP. This obligation applied even though the administrators took instructions on an execution only basis from the SIPP member and so did not have to advise on the suitability of the investment to be effected through the SIPP for the particular client.

The case arose following an application by Mr Charlton to Berkeley Burke to transfer his personal pension to a SIPP administered by them and to invest in a green oil scheme in Cambodia with the investment to be held within the SIPP. The investment failed as the oil scheme was a scam; the Cambodian company did not own the land it purported to have.

Mr Charlton complained to the Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) about Berkeley Burke's conduct and a final decision in his favour was issued by FOS in February 2017. Berkeley Burke applied for a judicial review of that final decision.

In its decision, the Ombudsman had determined the complaint by looking at Berkeley Burke's regulatory obligations to decide if it had acted fairly and reasonably by accepting Mr Charlton's investment into his SIPP. The Ombudsman held that Berkeley Burke was obliged to comply with the Principles for Businesses and, in particular, Principle 2 (acting with due skill, care and diligence) and Principle 6 (paying due regard to the interests of its customers and treating them fairly). The Ombudsman found that Berkeley Burke should have looked carefully at the investment it was allowing Mr Charlton's SIPP to invest in. The Ombudsman found that Berkeley Burke's duties were wide ranging and onerous. In particular, Berkeley Burke should have identified that the investment was high risk, considered if it was appropriate for a pension scheme, ensured the investment was genuine, independently verified that the assets of the company Mr Charlton was proposing to invest in were real and secure, ensured the investment could be independently valued and ensured that the SIPP would not become a vehicle for a high risk speculative investment which was not secure and could be a scam.

The Ombudsman made it clear that he was not making a finding that Berkeley Burke should have assessed the suitability of the investment for Mr Charlton, as a financial adviser would be required to do, but rather that it should have conducted due diligence and concluded that the investment was not appropriate for Mr Charlton's SIPP.

On the judicial review application, the court held that the Ombudsman had not created new duties that had not been the subject of consultation and regulatory approval in the usual way. The court decided that the Ombudsman had simply reviewed the existing Principles for Businesses and applied them to the facts of the case.

The court then went on to consider if the Ombudsman's finding imposed a duty of enquiry which conflicted with COBS 11.2.19 R(1) which provides that where there is a specific instruction from a client, the firm must execute the order following the specific instruction. Berkeley Burke argued that it had received specific instructions from Mr Charlton to acquire the asset and COBS 11.2.19 R (1) required them to implement those instructions.

The court held that there was no conflict between the application by FOS of the Principles for Businesses and COBS. The court found that COBS 11.2.19 R (1) applied to the way in which orders were to be executed; it did not apply to whether the order should have been accepted for execution in the first place. COBS 11.2.19 R (1) had to be construed harmoniously and consistently with the Principles for Businesses. Any suggestion that a SIPP provider must execute a transaction regardless of the duties imposed by the Principles, the court found could not be right. The obligation to execute an order did not override the Principles for Businesses and the question of their application to the particular circumstances of a complaint was a matter for the Ombudsman.

Finally, Berkeley Burke had argued that the Ombudsman had erred in declining to follow prior decisions of the Pension Ombudsman Service which had previously and repeatedly rejected similar complaints by consumers. The court found that the statutory schemes under which the Pensions Ombudsman Service and the Financial Ombudsman Service operated were different and this was fatal to any challenge based on the principle of consistency. It was open to FOS to consider the relevant facts of the complaint before it and come to a decision, applying the FOS's statutory framework, fairly and reasonably in all the circumstances of a case.

The claim for judicial review was therefore dismissed. The case is currently being appealed but pending the appeal, SIPP providers will be wise to consider carefully if the investment instructions they are executing should be accepted into the SIPP where a proposed investment is unusual or higher risk.

Vicarious liability for agent's fraud

Frederick v Positive Solutions (Financial Services) Limited [2018] EWCA Civ 431

This was an appeal to the Court of Appeal concerning a decision granting summary judgment to Positive Solutions in claims brought by Mr Frederick and others alleging that Positive Solutions was liable for the fraud perpetrated by its agent

The claimants had been persuaded by a Mr Qureshi to make short term loans to a property development scheme run by his business partner, Mr Warren. In return for the loan, the claimants would purportedly receive a fixed return on their investment and the return of that investment.

The loans were funded by re-mortgages of the claimants' respective properties arranged by Mr Warren. Mr Warren was also an IFA employed by Positive Solutions, although he was not its appointed representative so that section 39 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 was inapplicable. Mr Warren made the necessary applications for the mortgages based on false information and using Positive Solutions' portal with Abbey National but outside of Positive Solutions' normal business processes. The claimants did not have direct dealings with Mr Warren but said they derived comfort from the fact that he was FCA-regulated.

Mortgage offers were issued by Abbey National which stated that the mortgages had been arranged by Positive Solutions. Positive Solutions did receive commission on the mortgages but because this could not be related to any transactions arranged with their knowledge, the commission was held in a suspense account. The mortgage monies raised were used to pay off the claimants' existing mortgages with the balance being advanced to Mr Warren or a company in which Mr Warren and Mr Qureshi were directors. The money was misappropriated and/or lost in the property development scheme.

Positive Solutions brought a strike out application, alternatively sought summary judgment in relation to the claim brought against them on the basis that it was not vicariously liable for Mr Warren's conduct in the circumstances nor did it owe the claimants a direct duty of care. His Honour Judge Dight found in favour of Positive Solutions and the claimants were given permission to appeal to the Court of Appeal.