For nearly 30 years, more than just word marks have been capable of registration across the European Union (EU). The relevant statutory provision in the UK as to what can constitute a trade mark (at the relevant time) was section 1(1)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (the TMA), which read as follows:

“(1) ...a “trade mark” means any sign capable of being represented graphically which is capable of distinguishing goods or services of one undertaking from those of other undertakings. A trade mark may, in particular, consist of words (including personal names), designs, letters, numerals or the shape of goods or their packaging...".

This legislative change arose because of a recognition that what the public treats as 'branding', and what they therefore would perceive as distinctive of one business over its competitors, extends far beyond just words into anything which can serve as the basis by which the public makes such an association. Nevertheless, as a host of decisions have already demonstrated – most notably those that show the failure of Cadbury to retain exclusivity for the purple colouring of its packaging – these 'non-traditional' (ie non-word) marks face specific hurdles when their owners seek registered protection.

Recently, a decision of the High Court dealing with BabyBel's iconic waxed, torus-shaped cheese snack has confirmed the care that owners must take when seeking to register marks, in particular where colour is a key feature of the branding. The snack was introduced into the UK in 1981 where it has proved to be extremely popular, such that in 2017 over a billion of such products were consumed in the UK and it now accounts for nearly a quarter of the £220 million plus 'cheese snacking' market.

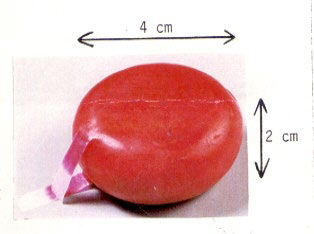

Unsurprisingly, soon after the enactment of the TMA in 1996, Fromageries Bel SA (FBSA) – who also manufacture BOURSIN, LEERDAMMER and LA VACHE QUI RIT – applied to register for 'cheese' in Class 29 a three dimensional representation of the cheese snack as depicted below:

In addition to the representation above, the application was accompanied by a description that stated '...The mark is limited to the colour red. The mark consists of a three dimensional shape and is limited to the dimensions shown above....'. The mark became registered in August 1997.

Revocation action

Twenty years later in 2017, the major retailer, J Sainsbury Plc (Sainsburys) applied to the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) seeking that the registration be declared invalid and thus revoked.

Sainsburys employed various arguments in support of its application, and one of these succeeded – namely that the phrase '...the colour red...' in the description did not provide sufficient clarity and precision. On this point, the Hearing Officer, having held that the colour red along with (i) the shape of the product in the dimensions indicated and (ii) the protrusions making the pull tag, were essential characteristics of the registered trade mark, agreed with Sainsburys and held:

'....I have reached the view on the balance of probabilities that the trade mark could be capable of distinguishing only if a particular hue of red used on the main body of the product is associated with FBSA's cheese. It follows that the trade mark must be limited to a single hue of red…'[paragraph 78].

Legal framework

Section 3(1)(a) of the TMA states that:

"(1) The following shall not be registered: (a) signs which do not satisfy the requirements of section 1(1)" (as above),

whereas section 47(1) of the TMA states:

'....The registration of a trade mark may be declared invalid on the ground that the trade mark was registered in breach of section 3 or any of the provisions referred to in that section (absolute grounds for refusal of registration)...'

What constitutes 'graphic representation' was addressed by the European Court of Justice (the CJEU) in Sieckmann v Deutsches Patent und Markenamt (Case C-273/00), which ruled that the representation of the mark can be by way of any graphic means (particularly images, lines or characters) but such had to be '...clear, precise, self-contained, easily accessible, intelligible, durable and objective...' (the Sieckmann Criteria). Moreover, since a subsequent ruling of the CJEU in the case of Libertel Groep BV v Benelux-Merkenbureau (Case C-104/01), the accepted practice of representing colour marks has been by reference to some internationally recognised identification codes, eg Pantone codes.

Grounds of appeal

FBSA appealed to the High Court the decision to invalidate the registration, setting out three grounds:

- The Sieckmann Criteria apply only to colour marks per se, not as here, where colour is just one of a number of the essential characteristics that comprise the mark.

- The UKIPO Hearing Officer should have interpreted the phrase the 'colour red' as being limited to the fuchsia/cherry hues of red as shown in the image of the snack that accompanied the application.

- Failing a successful appeal under grounds 1 and/or 2 above, in accordance with section 13(1)(b) of the TMA, FBSA should be entitled to have the registration amended such that the description is changed so that the colour red is limited only to those hues covered by Pantone No. 193C.

The decision

The High Court upheld the findings of the UKIPO and confirmed the cancellation of the registration.

HHJ Hacon held that the Sieckmann Criteria (which in that case involved an olfactory/smell mark), applied to the graphic representation of all trade marks – not just colour marks per se. Nevertheless, the judge accepted that whether or not the Sieckmann Criteria were satisfied will depend on the facts and, in particular, the interplay between the Sieckmann Criteria and the requirement that the mark has to be capable of distinguishing the goods or services of one undertaking from those of another. In some cases, the particular hue used in the mark might not play a significant role and the hues could vary "...without affecting the mark's capacity to distinguish....' [para 66]. However, that might not necessarily be the case.

'It seems to me that where a mark contains a colour but is not a colour per se mark, the need for precision as to hue will depend on the extent to which other elements of the mark serve to make the mark capable of distinguishing. More exactly, it will depend on the extent to which the colour of the relevant feature of the mark contributes to making the mark capable of distinguishing and whether it is likely that only a particular hue will confer on the mark that capacity to distinguish. It will always be a question of fact and degree...' [para 67].

The judge held that a fourth essential characteristic of the mark was the '..fuchsia colour of the pull tags fading to white at their ends...'. [para 70]. He also concluded that the public rely on other features of the manner by which the product is marketed, such as the prominence of the netting in which it is sold, the outer cellophane wrapper and the other labelling that contains the BABYBEL name in a particular script.

Accordingly, the judge rejected the first ground of appeal in that he had '…reached the view on the balance of probabilities that the trade mark could be capable of distinguishing only if a particular hue of red used on the main body of the product is associated with FBSA's cheese. It follows that the trade mark must be limited to a single hue of red…' [paragraph 78]

The judge also rejected the second ground of appeal, namely that the registration should be interpreted as being limited to the hue used in the picture because (i) the picture should not take precedence over the description; (ii) the description specified 'red', not any particular hue; and (iii) the description did not state that the red colour was as represented in the picture. As such, the reader of the registration must be taken to assume that the description covers all hues of red and, if this is not the case, the description would by definition, be inconsistent with the picture and would thus violate the Sieckmann Criteria in that clarity and precision would be absent.

Having found against FBSA on the first two grounds of appeal, the judge then considered whether FBSA would be permitted to limit its rights under the registration to the specific Pantone Code No. 193C – being the colour as depicted in the image of the product. Under section 13(1)(b) of the TMA, an applicant for or proprietor of a registered trade mark, may '...agree that the rights conferred by the registration shall be subject to a specified territorial or other limitation...'.Unfortunately for FBSA, the High Court also rejected this appeal and in doing so cited the Court of Appeal decision in Nestle SA's Trade Mark Application [2004] EWCA Civ 1008, which had held that section 13(1)(b) of the TMA could not be used to make a mark distinctive by affecting the description of the mark. In the Nestle case, in order to salvage the application for the shape of a mint without the POLO mark embossed on such (which had been deemed not to be capable of distinguishing the proprietor's products), the proprietor had attempted unsuccessfully to use section 13(1)(b) to limit the product as shown to white and a given size. Here, the judge held that limiting the registration to Pantone Code No. 193C would not only limit the scope of protection, it would also alter the description of the mark and therefore was not permissible.

The judge also commented that the Hearing Officer should have found that the fuchsia colour of the pull tags, which was not red, provided an additional reason for the mark lacking clarity and precision, as the description did not match the pictorial representation.

Comment

Even if the mark is not a colour mark, if colour is likely to be regarded as an essential feature of the mark, the applicant should be clear, precise and specific (whether via reference to Pantone codes or else by a clearly defined description) as to the hues that the registration is meant to cover.