18 November marks Equal Pay Day, the date from which (on average) women work without pay for the rest of the year as a result of the gender pay gap. Since April 2017, it has been compulsory for large employers (those with 250 or more employees) to publish a gender pay report each year. To what extent has this been effective in closing the wage gap between men and women?

Background

The pay gap is the difference in average hourly earnings – excluding overtime – between male and female employees, as a proportion of men's average hourly earnings. A positive figure means that, on average, men are being paid more than women, and a negative figure indicates that women are better paid.

According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the gender pay gap is reducing slowly over time and has fallen by a quarter over the last decade. However, the Fawcett Society estimated in 2019 that it would take 60 years for the pay gap to close completely.

Latest figures

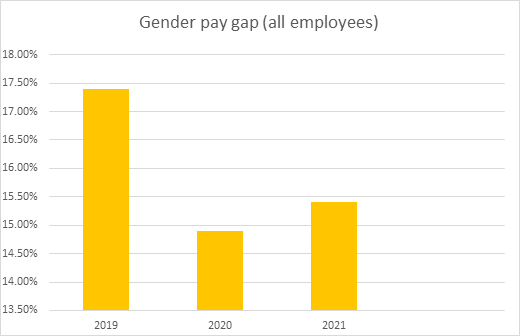

The ONS published its Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings on 26 October 2021. This is separate from compulsory gender pay gap reporting and showed that wage inequality worsened during the pandemic. The figures for the last three years are shown below.

The pay gap was highest for the top 10% of earners and older workers. There is a continuing theme of the gap being highest as between female employees aged between 40 and 49 who work full time and their male counterparts.

The increase in 2021 is partly due to the fact that more women than men were furloughed. The ONS warns that the 2021 figures were skewed by the pandemic, both as a result of the furlough scheme and because of challenges in collecting data, so we should not read too much into the increase. We will have to see if the downward trend continues when the next set of figures is published.

Closing the gap

A recent poll by jobs site Indeed found that 40% of teenagers would consider refusing to work for an employer with a gender pay gap. In an era of skills shortages and an applicant-friendly jobs market, it is possible that candidates will vote with their feet and will bring about a change in pay practices.

In the meantime employers can take proactive steps to reduce their pay gap, for example by expanding flexible working. The current consultation on the proposed changes to the law on flexible working arrangements may well force the issue as employees are likely to acquire the right to request flexible working as a day one right (without having to work for six months before being able to do so, as is the current position). Other measures that would help to eradicate the pay gap include not asking candidates about their previous salary (as this bakes in lower pay for women) and having transparent pay structures, where pay is fixed rather than being negotiable, there being ample evidence that women do not do as well as men in negotiating higher rates of pay.

Future developments

The Government is due to carry out a formal review of the gender pay gap reporting legislation next year, following which some reforms may be made. Possible changes include lowering the reporting threshold, a legal requirement to publish an action plan to make the changes necessary to tackle gender pay gaps, and the extension of reporting to include ethnicity pay gap data.

This article is for general information only and reflects the position at the date of publication. It does not constitute legal advice.