Why Big Tech Wants Your Body

Jan 12 2021

Your body may be a wonderland or a wasteland, but it is a goldmine of data.

Collectors of information have noticed. In our midwinter exploration of the economic and legal foundations of data regulation, we next turn to a natural tool for personal identification, for ongoing transactions (like breathing, walking, and heartbeats), and for categorization – your body. Big tech wants your body, and apparently, we are willing to offer our bodily data upon the altar of big tech.

Regulators know this and are beginning to address biometrics – the measurements taken from our physical presence – in law. States like Illinois, Texas, and Washington have laws requiring permission of the data subject for the capture and use of certain biometric indicators. The European Union classifies biometric information as sensitive data and companies and governments are fined for capturing this data outside the strict rules.

We have all read about privacy concerns with fitness technology. Locations of secret military bases revealed by the public display of soldier’s running/exercise routes on fitness tracking apps. Divorce lawyers and suspicious lovers using fitness tracking data to find cheating spouses. (NFL Network correspondent Jane Slater discovered her ex-boyfriend’s fitness monitoring proving too much sweating and heavy breathing away from home in the wee hours of the morning – Slater wrote, “His physical activity levels were spiking. Spoiler alert: He was not enrolled in an Orangetheory class at 4 a.m.”) I’m certain law enforcement officials this week are using fitness trackers and smartphone geolocation to confirm the locations of the U.S. Capitol rioters caught on camera (preserved on Bellingcat) and identified with facial recognition software. Criminal charges will follow.

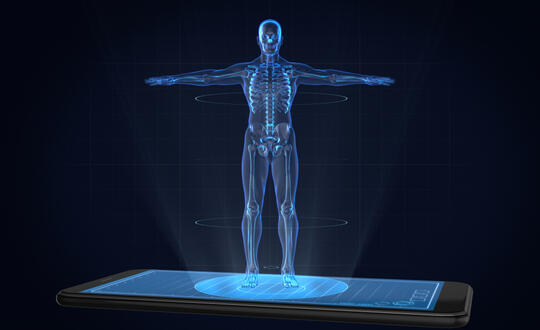

But many people don’t know how a collection of physical information about your body can be used by large tech companies. Facial recognition software has become controversial, but there is no reason that the government couldn’t create a database with body measurements as a foundation. Some security programs use gait recognition and matching. The way you move through space is as unique as a fingerprint, and computer software has been developed to compare the walk of a masked bank robber with the walks of the police’s suspects of the crime. The Chinese government has developed gait recognition software as part of its population control measures.

Virtual tailoring can be important in a pandemic, when you may not want to visit someone who will be close enough to measure your neck and inseam. The MTailor app uses smartphone cameras to customize clothes for the past six years.

Amazon has been especially keen to take your body measurements. In the fashion selfie app that Amazon Shopping Service closed down last year, its Halo fitness app which the Washington Post cited as the most intrusive tech it had ever tested, to the new clothes sizing app that claims to customize shirts just for you, Amazon has been producing “consumer benefits” that require us to submit measurements to the company. The newest tech “uses your height, weight, and two photos to create a precise fit” for clothes that you would order from Amazon. According to the Washington Post, the Halo fitness tracker “tells you everything that’s wrong with you. You haven’t exercised or slept enough, reports Amazon’s $65 Halo Band. Your body has too much fat, the Halo’s app shows in a 3-D rendering of your near-naked body. And even: Your tone of voice is “overbearing” or “irritated,” the Halo determines, after listening through its tiny microphone on your wrist.” Too much truth may be frustrating for all but the most masochistic of consumers. But Amazon benefits from all of this data.

For the clothing app, Amazon deletes the pictures you send to assist in the sizing, but it keeps the data that includes a virtual model of your body. This information can clearly be helpful for the described function, but it serves other purposes as well. If this information falls into your data aggregation file, held by and on behalf of information management companies everywhere, it can be used both to identify you by body type and specific body information, but to keep tabs on the changes in your body shape over time. This could trigger sales contact based on assumptions of pregnancy, illness, or other health emergencies, or even age. Whether your body shape changes over time can lead to assumptions about a fitness routine, consumption, and lifestyle issues. Companies like Amazon will make sales suggestions – books, vitamins, workout equipment, diapers – based on these assumptions. Target operated a 20,000 3-D body scan survey in Australia and is likely to use that information for analytics of all kinds. Some companies will identify you by your body movement.

Some will use body information to sell you things or to combine that data with other information that places you in helpful sales categories – for example, a fit, active 20-year-old will receive different sales pitches than a heavy, sedentary 50-year old. And we will only ever see the tip of the iceberg. For example, Microsoft has applied for a patent that would use body movement and facial expressions to evaluate the success of business meetings. The possibilities are endless. And, as discussed in my blog posts from the past two weeks, body data provided to Amazon, Target, or other companies can be used by that company for almost any reason.

Your body may belong to you, but the story it tells belongs to big tech.