Good Artists Copy; Great Artists Steal - Supreme Court Seemingly Narrows First Factor of Fair Use In Copyright Suit, Leaving Unanswered Questions For Artists and AI

May 22 2023

Listen to an audio summary of this alert in the player below or continue scrolling to keep reading.

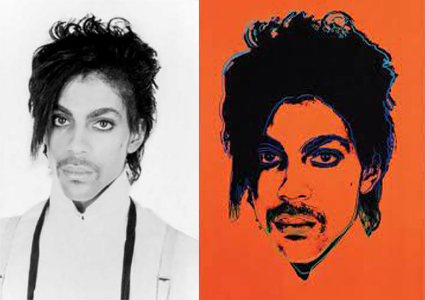

On May 18, the Supreme Court addressed the issue of “fair use” in copyright law, specifically in relation to the petitioner Andy Warhol Foundation’s (AWF) commercial licensing of a Warhol print entitled “Orange Prince” based on respondent Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the artist Prince Rogers Nelson, better known simply as “Prince.” The opinion focuses solely on the first fair-use factor, which examines “the purpose and character of the use, including whether it is of a commercial nature....” AWF contended that its use was “transformative,” and that the first factor therefore weighed in its favor, because the work conveys a different meaning or message (to comment on the “dehumanizing nature” and “effects” of celebrity) than the photograph (which conveyed Prince as a vulnerable, uncomfortable person). While the district court agreed with AWF, the court of appeals did not and reversed the lower court’s decision. The Supreme Court affirmed the appeals court’s decision, holding that, within the context of AWF’s use, AWF did not alter its purpose and character from Goldsmith’s photograph enough. In so concluding, the decision sparks discussion about the potential implications for copyright law, the art industry at large, and use of copyrighted material in artificial intelligence (AI).

The 7-2 majority found that adding new expression, meaning, or message does not automatically qualify a secondary use as transformative and fair. While relevant in the first factor fair use analysis, it is not, by itself, enough. Rather, the majority opined that the first factor asks “whether and to what extent” the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original. In the same vein, the Court held that the commercial nature of the use is not dispositive either, but it is relevant and should be weighed in the same way.

The Court reasoned that many secondary works add something new, and that newness, alone, cannot render such uses fair because if that were the case, it would undermine the copyright owner’s exclusive right to prepare derivative works. Many derivative works, such as musical arrangements, film adaptations, and even sequels, introduce new elements. To make its point, the Court relied on its precedent that drew a distinction between parody and satire. Parodies target the author or work for humor or ridicule, while satires ridicule society in general but do not necessarily target an author or work, thus, are capable of standing on their own. Parodies are usually “transformative” while satires may not be. The dissent did not understand why this should be the deciding factor.

The dissent accused the majority of contradicting the Court’s recent precedent in Google v. Oracle. In Google, the Supreme Court found Google’s use of Sun Microsystems’ computer code (purchased and owned by Oracle) constituted fair use, despite literal copying being used for a commercial purpose. The dissent understood Google’s explanation of the first fair-use factor to balance solely on the creativity and innovation of the secondary use, which is enough for the secondary use to have infused the original with new expression, meaning, or message. The majority interpreted Google in another way: in spite of Google’s outright copying of a portion of Sun Microsystems’ code, Google used the code, originally intended for computers, in a distinct and new environment when it created its own Android smartphone platform. In sum, the purpose and character of the code in Google’s secondary use, even for commercial gain, transformed the original code enough to avoid infringement.

The Supreme Court’s opinion underscores the need for a contextual analysis of fair use on a case-by-case basis. As Justice Neil Gorsuch’s concurrence explains it: “By its terms, the law trains our attention on the particular use under challenge” rather than focusing on the subjective intent of the artist who created the original work. In other words, fair use is a flexible concept that can vary depending on the specific context and type of copyrighted material involved. For example, as the Court reiterated a number of times, its analysis in this case is limited to this specific use of Orange Prince: AWF’s commercially licensing the image to a magazine for a special memorial issue after Prince’s death. The majority expressed no opinion on the creation, display, or sale of any of Warhol’s Prince Series works (there were 16 total, including the Orange Prince), leaving open the possibility that other uses of the same print may be protected by fair use (e.g., displaying the image in a nonprofit museum or use in a for-profit book commenting on 20th century art). This means that the same act of copying may be considered fair in one context but not in another.

Left: Lynn Goldsmith’s photograph of the artist Prince

Right: "Orange Prince" by Andy Warhol

Turning to another issue of particular interest in a world currently supersaturated with AI news, what does this decision mean for the use of copyrighted works in AI-generated content? There are several lawsuits pending right now that involve using copyrighted works as training data for AI. One of the cases is centered around generating outputs that replicate the style or essence of the copyrighted works fed into the AI. The first factor of fair use may turn on how the AI-produced work is ultimately used (assuming the AI is capable of creating something “substantially similar” in the first place) rather than the subjective intent of the coder-“artist.” Courts will have to ask with regard to the first fair use factor whether the new work is being used to supplant the original work, or whether, for instance, an AI-generated image is being used as a commentary or critique on the original author’s work. What about in the case of publishing a work “in the style of” a renowned artist like “Drake” on social media to gain a massive following?

For clients looking to protect their copyrighted works and understand the contours of fair use, the WBD team stands ready to guide clients through these developments in copyright law. For further information, please contact the authors of this alert or the WBD attorneys with whom you normally work.