Take Video, But Secure a Warrant to Run Facial Recognition Software

Jun 16 2020

Last week’s tech company announcements about facial recognition software startled me, but probably not for the reason you might imagine.

Amazon, IBM and Microsoft all boosted their socially conscious credibility by moving to restrict local police and federal law enforcement use of their facial recognition technology for the near future. Their aim apparently is that more protesters can achieve the security by obscurity that most of us expect in crowds with less law enforcement bodies able to scan and identify individual protesters, or, even worse, identify all the protesters at a site.

This is a good thing, right?

New IBM CEO Arvid Krishna wrote to Congress about why IBM was proposing to break its government contracts, concerned that police would use the tech to violate basic human rights. Amazon used a company blog post to announce its own suspension of police access to Rekognition, its facial recognition software, for a year. Microsoft then said it would suspend sales to law enforcement agencies until federal regulations on use of facial recognition software are in force.

Last week, noting the same concerns that led to these decisions, I wrote a post questioning why U.S. national or state legislatures – seemly in thrall to police lobbies and ‘law and order’ shaming – hadn’t placed some limits on the combination of constant surveillance and A.I.-based identity programs for law enforcement. While my comments still stand, at least the private sector has moved to limit the persistent drive toward a total surveillance state.

So why the concern?

I saw these headlines and thought, “Wait a minute, Amazon, Microsoft and IBM all sell facial recognition software to the police? That’s lots of firepower. Who else might be doing this?”

We all know about Clearview AI. This company has made it very clear that it will continue offering facial recognition services to anyone who pays, especially law enforcement. Japanese tech giant NEC just recommitted its salesforce to supplying U.S. law enforcement with facial recognition software according to the Wall Street Journal. The same article notes that “’Most of the major companies that have the most contracts with law enforcement for facial recognition are smaller, specialized companies that most people have not heard of,’ said Jameson Spivack, a policy associate at the Center on Privacy and Technology at Georgetown Law.” It then pinpoints Ayonix Corporation as another that has reaffirmed its plan to sell to police, along with iOmniscient and Herta Security LLC.

Washington Post tech writer Geoffrey A. Fowler identifies Idemia as another major player in supplying biometric identification tech to law enforcement, and he echoes my call from last week writing, “The only thing that’s really going to stop police from using the tech is new laws.” We are both right about this sentiment, because we know how many companies are needed to provide the tools that law enforcement can use to intimidate a lawful assembly – just one.

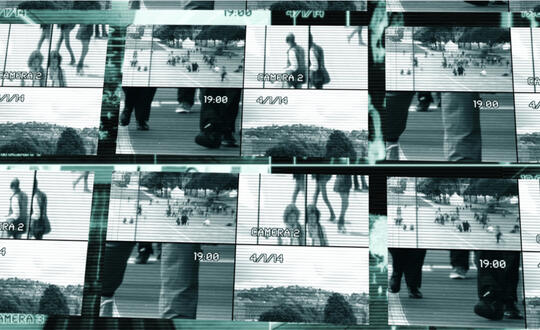

The only fix that will restrict this surveillance activity is to require warrants or other court permission – where the tech can only be used if there is at least a reasonable suspicion that a crime has been committed. This would not be a burden on police. The ballooning population of surveillance cameras will continue to catch activity, but we need to restrict police from identifying every person they see on the footage, just because they want to do so. If there is a need, get a warrant, run the software, and identify that person holding a protest sign or walking across the street. If you can’t establish a good reason to run the identifying software, don’t do it.

I have written repeatedly about the fact that the police will take as much leeway as our legislators are willing to give them. That is a reasonable position for law enforcement officer to take – use all resources at your disposal. But our current crisis with regard to intrusive surveillance tech in part arises from the fact that, since the Reagan years, but certainly post 9/11, no one in power has been willing to provide any reasonable limits on the reach of policing. Compared to twenty years ago, law enforcement has dozens of new tools at its fingertips, which have been popularized in a time when our society was not willing to put limits on how they could be used.

The Post’s Fowler seems more concerned that facial recognition technology does not work well for disadvantaged populations. I am most concerned about where the tech is working exactly as intended – stitching names to the faces in the crowd exercising their Constitutional rights to speech and assembly.

But one of Fowler’s other points is vital. The big tech companies may be taking their current stance to take pressure off of legislatures to regulate this industry. Some tech companies have already been active in proposing rules for surveillance tech that privacy activist see as watered down and ineffective. According to Jameson Spivack of Georgetown Law’s Center on Privacy and Technology, the tech companies are “lobbying for bills that might look to a lot of people like they’ve got really strict protections. But then, if you actually look at them, they don’t really actually regulate the technology much as it’s used.”

If you are want to see the effects of surveillance of protests without limits, observe the recent protests marches in Hong Kong against the deepening consolidation of single-state power in the territory. People are taking drastic countermeasures from full-body masking to pulling down the government’s cameras, because they know what happens in the rest of China when the government identifies you as a troublemaker. Prison is a possible outcome, but so is government restriction on career, housing and other markers of a normal life.

There is no need to take the comparison too far. The U.S. is not China. And this country may be awakening to an important way for emphasizing distinctions between the two societies – our democratically elected leaders are able to place restrictions on surveillance that the courts will enforce and the police will respect. We simply need the political will to act like a free democratic society and impose some requirements for legitimate law enforcement reasons to run powerful identification software on captured video. Who will stand up first?