Proposed Alternative PTAB Discretionary Denial Factors In View of Co-Pending Parallel Litigation

Oct 02 2020

This article originally was published by Law360.

The authors propose replacing the PTAB’s current NHK-Fintiv factors with the alternative “Babcock-Train Factors” set forth herein.1 These alternative factors have been crafted in an effort to provide clearer institution guidance to the PTAB’s Administrative Patent Judges (“APJs”), and to afford a neutral perspective with respect to both the particular posture of the party in the PTAB proceeding (petitioner or patent owner) and the specific venue of the parallel district court litigation.

To be clear, the authors do not suggest that these alternative factors should be the definitive guidelines promulgated by the USPTO. Rather, they are proposed to initiate a dialog among PTAB stakeholders. Refinements, revisions, and improvements to this proposal are both likely and welcome, especially given the collective experience and varied perspectives of the diverse PTAB community. But the authors hope that this proposal will provide a basis for a productive continuing dialog on an important and increasingly controversial issue.

There can be little legitimate dispute that Congress provided the Director with discretion to deny institution of an IPR/PGR/CBM proceeding. 35 U.S.C. § 314(a). But Congress was largely silent regarding the precise manner in which the Director should exercise that discretion, as well as the particular rules that should be promulgated for doing so. Certainly, the Administrative Procedures Act provides constraints on the Director’s discretion, but (of course) those limitations are not specific to the PTAB’s institution decision.

Over the course of its post-AIA existence, the PTAB has established jurisprudence for exercising its discretion to deny petitions procedurally, including promulgating the seven General Plastic factors2 for evaluating so-called “follow-on” petitions (under Section 314(a)), and the six Becton Dickinson factors3 for evaluating arguments and evidence previously considered by the USPTO (under 35 U.S.C. § 325(d)).4 More recently, the PTAB has adopted the NHK-Fintiv factors to support discretionary denial of IPR petitions based on parallel district court litigation, which has generated considerable discussion within the PTAB bar and beyond.5

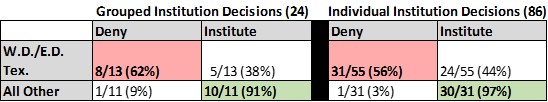

The authors have recently conducted a statistical analysis of the Board’s invocation and application of the NHK-Fintiv factors to provide some insights into how the PTAB evaluates and weighs each of the six NHK-Fintiv factors from a macro perspective, irrespective of the specific and unique facts of each case.6 That study, together with the further analysis discussed herein, indicates that the current set of NHK-Fintiv factors is not venue-neutral, significantly disfavoring petitioners who are defendants in so-called “fast track” district courts, such as the Eastern and Western Districts of Texas.7 In particular, expanding that previous statistical analysis to consider the specific venue of the parallel district court litigation reveals that cases pending in those two Texas venues are far more likely to receive a discretionary denial of institution from the PTAB’s application of the NHK-Fintiv factors than are cases pending in all other venues. The supplemental statistical chart shown below in Table 1 reveals this stark contrast, where cases pending in the two Texas venues are more likely than not to have PTAB petitions discretionarily denied, as opposed to cases pending in all other venues that are exceedingly unlikely to have PTAB petitions denied:8

Moreover, the NHK-Fintiv factors have proven to be vague in some respects and overlapping in focus, and the manner of briefing and analyzing these factors (particularly by PTAB practitioners) has often been conflicting and/or imprecise.9 From the authors’ perspectives, the sudden importance of the NHK-Fintiv factors has engendered time consuming and expensive ancillary disputes—frequently in the form of reply and sur-reply briefs—with the parties often disagreeing not only on the relevant facts that should be considered, but also on the proper manner in which to conduct of the NHK-Fintiv analysis.

The PTAB elevated the NHK-Fintiv factors to “precedential” status on May 5, 202010 (having elevated the NHK decision to that status about a year earlier),11 and the impact of that decision has since reverberated loudly within the PTAB bar and beyond.12 Intriguingly, the NHK-Fintiv analysis has even elicited respectful dissent from within the APJ bench, which is rare for the PTAB. In one notable example, an experienced and distinguished APJ13 dissented from the majority’s denial of institution in view of parallel litigation in the Eastern District of Texas, concluding his detailed analyses with the following lucid observations:

I also take note of Fintiv’s statement that our evaluation of the factors should be based on “a holistic view of whether efficiency and integrity of the system are best served by denying or instituting review.” Fintiv at 6. And in this sense, a weighing of individual factors aside, I cannot agree with the majority that denying institution here best serves the efficiency and integrity of the patent system. The Petitioner here did exactly what Congress envisioned in providing for inter partes reviews in the America Invents Act: upon being sued for infringement, and having received notice of the claims it was alleged to infringe, it diligently filed a Petition with the Board, seeking review of the patentability of those claims in the alternative tribunal created by the AIA. . . . The inter partes review would proceed, necessarily having a narrower scope than the infringement trial before the district court, and would resolve in an efficient manner the patentability questions so that the district court need not take them up. I fail to see how this outcome would be inconsistent with the “efficiency and integrity of the system.”14

While some parties have challenged the NHK-Fintiv analysis in its entirety,15 other stakeholders have acknowledged the PTAB’s statutory authority to exercise its discretion, but have nonetheless criticized the Board’s rulemaking process:

The Original Plaintiffs also ask this Court to set aside the current way the Director exercises such discretion because it did not arise through notice-and-comment rulemaking. This implicates the Small Business Inventors’ need for clear regulations promulgated lawfully by the Director that preserves and improves (not eliminates) the Director’s full powers of discretionary denial.16

―

The PTAB is increasingly refusing to institute otherwise-meritorious IPR petitions for purely procedural reasons. And it is doing so through self-declared precedential decisions that promulgate new PTAB policies without notice-and-comment rulemaking or the possibility of judicial review. . . . Congress could also encourage the PTAB to engage in traditional rulemaking when setting new policy for how and when to exercise its discretion, as the Federal Circuit and commenters have also indicated they should.17

―

Precedential decisions NHK and Fintiv have not translated to predictability. Both decisions provide “non-exclusive” factors that are to be “weighed” as a part of a “balanced assessment”. What does this mean? No one knows. How is a factor to be scored and how much weight does each get and what score will assure or prevent denial of institution? A sample of recent institution decisions illustrates the problem....

There are many other apparently conflicting decisions which are altogether undecipherable. The analysis under NHK and Fintiv has only added complexity and unpredictability to the institution decision. Clear and unambiguous rules would alleviate this and achieve the intended purpose of §314(a) and §316(b).18

While the authors purposely do not weigh in on any pending litigation, PTAB proceeding, USPTO petition, or Congressional activity, they believe that it is likely that the USPTO will—at some point in the future, whether through formal rulemaking or otherwise—re-address the factors that the PTAB should consider in deciding whether to discretionarily deny institution of an IPR or PGR petition in view of co-pending parallel litigation.

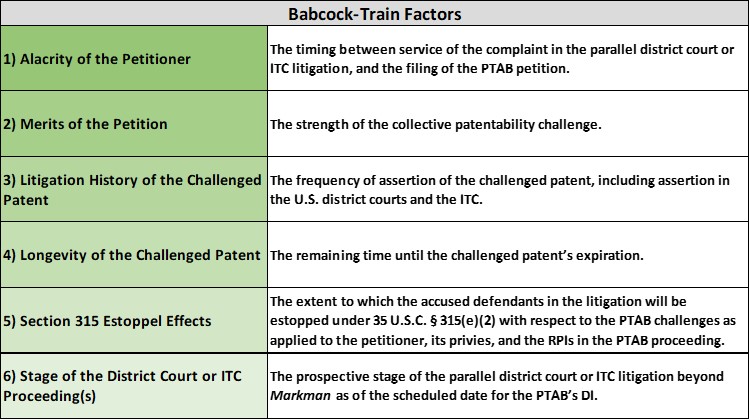

In light of the foregoing discussion, the authors propose that the PTAB de-designate the NHK-Fintiv factors as precedential authority,19 and in their place adopt (via formal rulemaking or otherwise) an alternative set of non-exhaustive discretionary denial factors as follows (in decreasing order of weight):

1) Alacrity of the Petitioner – The timing between service of the complaint in the parallel district court or ITC litigation, and the filing of the PTAB petition.

Guidance: The longer the petitioner’s delay beyond four (4) months of service of the complaint, the more this factor weighs in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa. Notwithstanding the foregoing, this factor should be nearly dispositive in favor of institution for timely filed PGRs.

Commentary: The petitioner should be afforded a reasonable opportunity after service of the complaint to evaluate the asserted patent and, inter alia, collect and review the prior art, consult with an expert witness, and prepare the petition and supporting declaration. The authors suggest that four (4) months (⅓ of the statutory 1-year time bar for IPRs under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b)) is a reasonable and expeditious time frame for filing a PTAB petition.

A PGR petition must be filed within nine months of a first-to-file patent’s issue date. 35 U.S.C. § 321(c). The AIA legislative history emphasizes the importance of having the PTAB review PGRs early in the life of the challenged patent, before expensive district court litigation ensues.20 Accordingly, the PTAB should have a very strong (and likely absolute) interest in reviewing a timely filed PGR petition.

2) Merits of the Petition – The strength of the collective patentability challenge.

Guidance: The weaker the merits of the collective patentability challenge, the more this factor weighs in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa. The term “collective patentability challenge” is used consistently with the PTAB’s institution analysis under the SAS Institute decision21 (i.e., at least one ground and one claim).

Commentary: The USPTO should have a strong interest in reevaluating an issued patent when the petition convincingly demonstrates that the challenged patent is, at least in part, defective. Elevating the merits-based consideration (from the catch-all Factor 6 in the NHK-Fintiv analysis) is essential in order for the USPTO to play its important patentability gatekeeper role as mandated by Congress in the AIA.

3) Litigation History of the Challenged Patent – The frequency of assertion of the challenged patent, including assertion in the U.S. district courts and the ITC.

Guidance: The more frequently the challenged patent has been asserted beyond one time, the more this factor weighs against discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: The USPTO should have a strong interest in reevaluating an issued patent when it has been asserted frequently, including formally (e.g., in the U.S. district courts and the ITC) and informally (e.g., cease and desist letters, which indicate a likelihood of future formal assertion). The potential for divergent district court and ITC claim construction and invalidity determinations highlights the USPTO’s role of providing a uniform patentability analysis. Further, the TC Heartland decision,22 which has resulted in the distribution of patent infringement cases in a significantly greater number of venues, increases the likelihood of divergent district court decisions regarding an asserted patent.

This factor assumes that the challenged patent has been asserted once, namely, in the co-pending parallel litigation. In addition, the inclusion of informal assertions in this factor is not intended to affect the PTAB’s limited discovery practices and public disclosure requirements. Rather, consideration of informal assertions should be permitted to indicate the potential for future litigation.

4) Longevity of the Challenged Patent – The remaining time until the challenged patent’s expiration.

Guidance: The shorter the challenged patent’s remaining life, the more this factor weighs in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: A patent with a longer life poses a larger potential for future disputes, and thus the PTAB should have a greater interest in evaluating a patentability challenge to a patent with a longer remaining term. The policy considerations for Babcock-Train Factor 3, as discussed above, also apply to this factor.

5) Section 315 Estoppel Effects – The extent to which the accused defendants in the litigation will be estopped under 35 U.S.C. § 315(e)(2) with respect to the PTAB challenges as applied to the petitioner, its privies, and the RPIs in the PTAB proceeding.

Guidance: The lesser the extent of the estoppel on the relevant parties, the more this factor weighs in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa. The Panel should disregard additionally named and/or omitted parties in the parallel district court or ITC litigation who do not materially affect the substance of the principal infringement and invalidity allegations. Also, the Panel should disregard any district court or ITC invalidity allegations that would not have been permitted in the PTAB challenge.

Commentary: Certainly Congress’ intent in establishing IPR and PGR reviews was to provide an alternative forum for evaluating certain patent validity (patentability) challenges, and generally to allow the petitioner with a single bite at that proverbial apple. To the extent that the PTAB proceeding will not effectively accomplish that “single bite” purpose, then the USPTO should have less interest in instituting trial. Note, however, that parties should not be able to “game” this factor by naming and/or deleting parties in the parallel district court or ITC litigation who do not substantively affect the principal infringement and invalidity allegations. And permissible district court or ITC validity assertions that would not be permitted in the PTAB challenge (e.g., a Section 101 challenge in an IPR) should not be considered in this factor.

6) Stage of the District Court or ITC Proceeding(s) – The prospective stage of the parallel district court or ITC litigation beyond Markman as of the scheduled date for the PTAB’s DI.

Guidance: The further the parallel district court or ITC litigation will have likely progressed beyond the Markman proceedings at the expected date of the DI, the more this factor weighs in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa. If the district court or ITC has granted a stay, this factor will weigh against discretionary denial, but not vice versa.

Commentary: In conjunction with Factor 1, this factor assumes that most parallel district or ITC cases will have been proceeding for about 10 months at the expected date for the PTAB’s Decision on Institution (“DI”), and thus have begun (and possibly completed) the Markman stage of the litigation. This factor also (realistically) assumes that most district courts will not grant a pre-institution stay given the steadily declining IPR/PGR institution rate (currently ∼55%),23 and that the ITC will rarely grant such a stay. But in consideration of efficiency and notice to the district court or ITC, defendants should be encouraged to seek a stay if they so desire, and they should not be penalized by the PTAB for doing so. This factor also neutralizes the impact of the district court’s or ITC’s Markman proceeding because the parties’ briefing, and the district court’s or ITC’s analysis, regarding claim construction under the common Phillips standard can be readily considered by the PTAB. 37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b).

A summary of the Babcock-Train Factors is provided in Table 2 below.

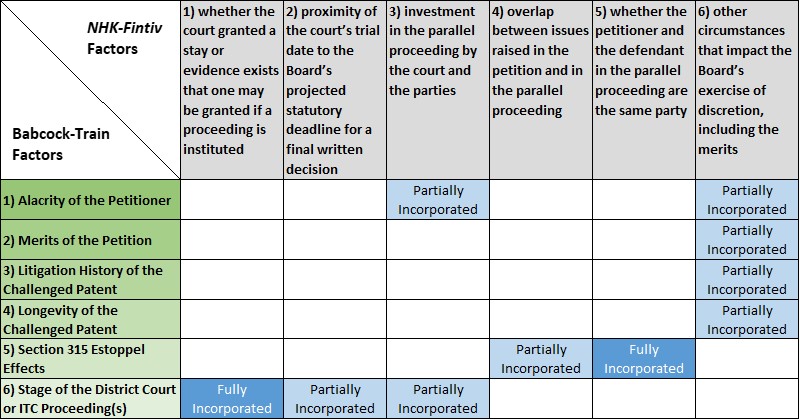

The alternative “Babcock-Train” factors set forth above are not oblivious to the considerations that prompted the PTAB to adopt the NHK-Fintiv analysis. Indeed, most of the salient considerations of the NHK-Fintiv factors have been incorporated into the proposed alternative factors.

NHK-Fintiv Factor 1 (“whether the court granted a stay or evidence exists that one may be granted if a proceeding is instituted”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been effectively incorporated into Babcock-Train Factor 6.

NHK-Fintiv Factor 2 (“proximity of the court’s trial date to the Board’s projected statutory deadline for a final written decision”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been effectively incorporated into Babcock-Train Factor No. 6. At the pre-institution stage, attempting to predict the timing of a district court’s future trial date is very speculative, often little more than an educated and partially informed guess about events more than a year in the future. District courts routinely schedule multiple cases for trial in the same time frame, reasonably expecting that many of those cases will settle at some point before trial (like airlines who routinely overbook flights based on statistical cancellation rates). Accordingly, trial dates are frequently postponed, either by the Court sua sponte or in conjunction with party stipulation.24 The PTAB should not engage in such error-prone speculation, and should not make an important institution decision based on information that is speculative and very likely to become inaccurate after the PTAB issues its DI.

The authors appreciate that proposed Babcock-Train Factor 6 (“stage of the district court proceeding”) would also require some speculation by the Board. But by shifting the focus from the distant trial date to the initial Markman proceedings, at the time of the POPR, the proposed forward-looking perspective is only 3 months (not 15 months), which is more likely to be ascertainable. Further, the parties are able to update the Board pre-institution through the submission of Supplemental Information (see 37 C.F.R. § 42.123(c)) or potentially other less formal means. In any event, the authors have included this factor last in the list, partly because of this implicit uncertainty.

NHK-Fintiv Factor 3 (“investment in the parallel proceeding by the court and the parties”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been incorporated into Babcock-Train Factors 1 and 6. By filing an expeditious petition (pre-Markman), the investment in the parallel proceeding should be significantly reduced compared to filing a petition on the one-year deadline, which has likely allowed the parallel proceeding to advance beyond Markman.

NHK-Fintiv Factor 4 (“overlap between issues raised in the petition and in the parallel proceeding”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been effectively incorporated into Babcock-Train Factor No. 5. In district court litigation, an accused infringer will nearly always assert one or more counterclaims for patent invalidity. If the accused infringer has filed a PTAB petition, those counterclaims will usually (not surprisingly) encompass the same challenges as set forth in the petition. Congress imposed estoppel on a petitioner and its privies only after the PTAB issues a Final Written Decision (“FWD”) (37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b)), so penalizing the petitioner earlier unfairly attempts to broaden the statutory estoppel. Pre-FWD, the petitioner should not be penalized for preserving its rights by raising those same arguments in the parallel district court or ITC litigation, and should not be effectively compelled to make some formal waiver of its litigation invalidity challenges by the PTAB.25

NHK-Fintiv Factor 5 (“whether the petitioner and the defendant in the parallel proceeding are the same party”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been effectively incorporated into Babcock-Train Factor 5.

NHK-Fintiv Factor 6 (“other circumstances that impact the Board’s exercise of discretion, including the merits”):

This NHK-Fintiv Factor has been incorporated into Babcock-Train Factors 1-4. While the authors propose that the Babcock-Train factors should be non-exhaustive, and thus do not suggest that the PTAB should be prohibited from considering other non-enumerated factors when raised by the parties and appropriate, a formal “catch-all” category should not be a discrete factor.

A general summary of the relationships between the NHK-Fintiv Factors and the Babcock-Train Factors is provided in Table 3 below. In that table, the authors have endeavored to illustrate where each NHK-Fintiv Factor has been fully or partially incorporated into one or more of the Babcock-Train Factors.

The authors hope that the “Babcock-Train” factors proposed herein will provide a solid basis for continuing the dialog regarding the manner in which the Board should—or should not—invoke its discretion to deny a PTAB petition in view of co-pending parallel district court litigation.

1 The authors’ naming of these factors reflects that the entire analyses herein are solely the personal views of the authors, and should not be attributed in any way to Womble Bond Dickinson or any of its clients.

2 General Plastic Indus. Co., Ltd. v. Canon Kabushiki Kaisha IPR2016-01357, Paper 19 (Sept. 6, 2017) (precedential, seven-APJ panel).

3 Becton, Dickson & Co. v. B. Braun Melsungen AG, IPR2017-01586, Paper 8 (Dec. 15, 2017) (informative).

4 The six Becton Dickinson factors, the seven General Plastic factors, and the six NHK-Fintiv factors have been aptly called the “Discretionary Denial Trilogy”. Bemben & Specht, Fintiv & Thryv Highlight PTAB-District Court Patent Litigation Interplay: Parties Must Heed the Discretionary Denial Trilogy, IPWatchdog (June 4, 2020).

5 E.g., McKeown, Congress Urged to Investigate PTAB Discretionary Denials, Patents Post-Grant (June 30, 2020); Unified Patents, PTAB Procedural Denials and the Rise of § 314 (May 13, 2020).

6 Babcock & Train, PTAB Factors for Instituting IPR: What the Stats Show, Law360 (Sept. 18, 2020).

7 See McKeown, supra note 5 (“The vast majority of discretionary denials under NHK are favoring aggressive trial schedules of Texas district courts.”); Unified Patents, supra note 5 (The NHK-Fintiv analysis “favors litigants who file first in districts with aggressive time-to-trial that are unlikely to stay cases in light of IPRs—like the Western District of Texas, which schedules Markman hearings six months after a case management conference, with trials roughly 18 month after the conference.”).

8 For purposes of the original statistical analysis, multiple IPRs involving the same parties but challenging different patents were grouped together as a single case when the PTAB issued institution decisions with the same analysis of the NHK-Fintiv factors. The venue analysis for those twenty-four grouped institution decisions is shown on the left, and the same analysis for each of the eighty-six individual institution decisions is shown on the right.

9 E.g., Kass, Tech Giants Are Putting PTAB's Discretion to the Test, Law360 (“Another big concern for PTAB critics is that panels haven’t been interpreting the factors in Fintiv the same across the board....”).

10 Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc., IPR2020-00019, Paper 11 (PTAB March 20, 2020) (precedential, designated May 5, 2020).

11 NHK Spring Co. v. Intri-Plex Techs., Inc., IPR2018-00752, Paper 8 (PTAB Sept. 12, 2018) (precedential, designated May 7, 2019).

12 See, e.g., Jones, USPTO Abuse of Discretionary IPR Denials Must Be Cabined, Law360 (Sept. 10, 2020).

13 Quinn, 8 New PTAB Judges Sworn in at USPTO, IPWatchdog (Nov. 12, 2012).

14 Cisco Sys., Inc. v. Ramot at Tel Aviv Univ. Ltd., IPR2020-00123, Paper 13, at 12-13 (May 15, 2020) (Crumbley, APJ, dissenting) (emphases added).

15 Apple Inc., Cisco Sys., Inc., Google LLC, & Intel Corp. v. Iancu, No. 5:20-CV-06128-EJD (N.D. Cal. Aug. 31, 2020).

16 Id., Intervenors’ Mot. to Intervene, Dkt. No. 28 at 8 (Sept. 14, 2020) (emphasis in original); see Brachmann, Tech Companies’ Lawsuit Against USPTO – and Small Business Inventors’ Motion to Intervene – Highlight Need to Address NHK-Fintiv Factors Via Rulemaking, IPWatchdog (Sept. 16, 202).

17 Letter from coalition of patent stakeholder organizations to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, at 1 & 3 (June 18, 2020) (https://www.eff.org/files/2020/07/29/2020.06.18_ipr_discretionary_denial_letter_sjc.pdf).

18 Petition for Rulemaking Pursuant to 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) for Specific Criteria for Deciding Institution of AIA Trials, USPTO (Aug. 27, 2020).

19 See Quinn, USPTO Announces That PTAB Precedential Decisions Can Be Anonymously Nominated, IPWatchdog (Sept. 25, 2020).

20 Congress intended for newly issued patents to be promptly reevaluated by the PTAB to “allow invalid patents that were mistakenly issued by the PTO to be fixed early in their life, before they disrupt an entire industry or result in expensive litigation.” 157 Cong. Rec. at S1326 (emphases added); see 153 Cong. Rec. at E774 (“In an effort to address the questionable quality of patents issued by the USPTO, the bill establishes a check on the quality of a patent immediately after it is granted.... The post-grant procedure is designed to allow parties to challenge a granted patent through a[n] expeditious and less costly alternative to litigation.”) (emphases added).

21 SAS Institute Inc. v. Iancu, 138 S. Ct. 1348 (2018).

22 TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC, 137 S. Ct. 1514 (2017).

23 USPTO, Trial Statistics: IPR, PGR, CBM (Aug. 31, 2020) (https://www.uspto.gov/sites/default/files/documents/trial_statistics_20200831.pdf).

24 See McKeown, District Court Trial Dates Tend to Slip After PTAB Discretionary Denials, Patents Post-Grant (July 24, 2020).

25 See NVIDIA Corp. v. Tessera Advanced Techs., Inc., IPR2020-00708, Paper 9 (Sept. 2, 2020); VMware, Inc. v. Intellectual Ventures I LLC, IPR2020-00470, Paper 13 (Aug. 18, 2020).