CHARLESTON, SC—US Army Sgt. Isaac Woodard served his country well, earning numerous medals and honors during World War II. All he wanted in return was a little respect when he returned home.

Sadly, such respect was not often granted to an African-American man in 1946—even a distinguished military veteran. Sgt. Woodard, still wearing his dress uniform, departed Camp Gordon in Augusta, Ga. on a Greyhound bus, heading for a long-awaited reunion with his wife in Winnsboro, SC. At one of the frequent stops, Sgt. Woodard asked to exit the bus to use the restroom—a request bus company policy said should be accommodated. But the driver cursed the returning veteran and told him to return to the back of the bus. He was not prepared for an African-American passenger to stand up for himself as Sgt. Woodard did.

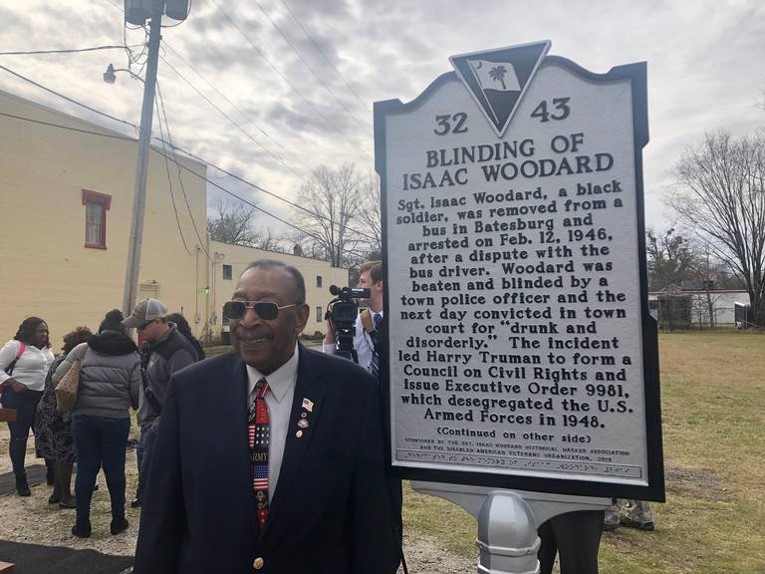

“Talk to me like I’m talking to you! I am a man, just like you!” Sgt. Woodard said. The stunned bus driver allowed him to go to the restroom. But at the next stop, in Batesburg, SC, the driver found a police officer and had Sgt. Woodard arrested.

A bad situation got much worse. When Sgt. Woodard tried to explain, local police chief Lynwood Shull beat him with a nightstick. The attack was so brutal that Sgt. Woodard was blinded in one eye. While such incidents were not uncommon in the Jim Crow era, they often received little attention from the nation at large. However, this attack was different, in that it attracted public attention all the way to the White House and federal courtrooms and proved to be a catalyst for change.

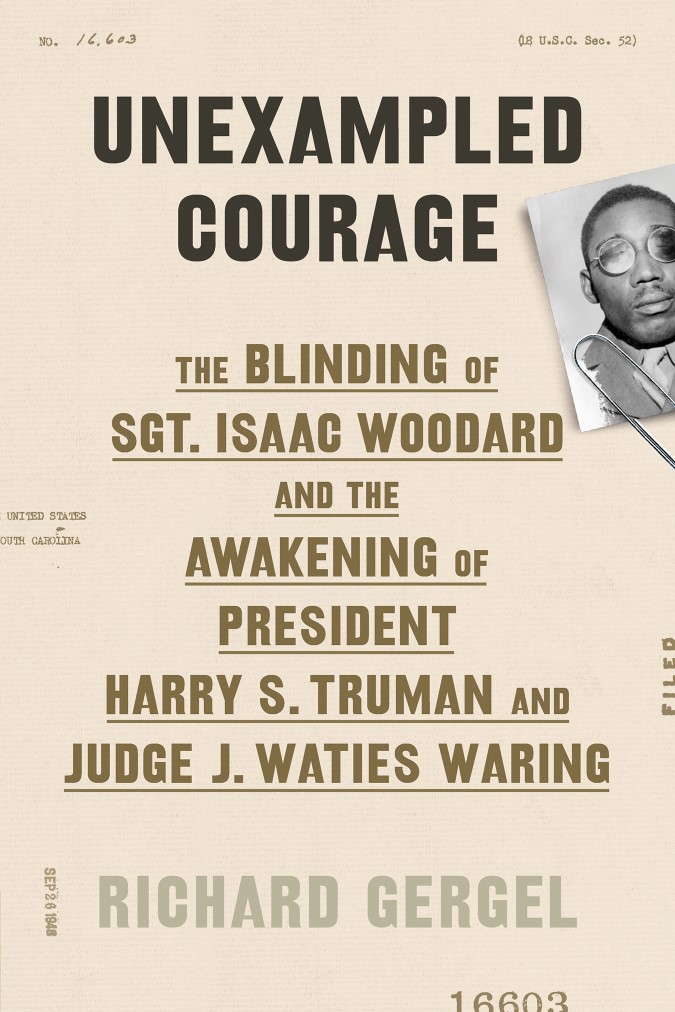

Sgt. Woodard’s story—and the impact it had on civil rights in America—are the subject of a new book, Unexampled Courage. The book was written by US District Court Judge for the District of South Carolina Richard Gergel, who served as the guest speaker for the Womble Bond Dickinson’s Feb. 21 Diversity Speaker Series event.

“Beneath the veneer of America’s grand self-image as the bastion of freedom and liberty was a stark reality. African-Americans residing in the old Confederacy lived in a twilight world between slavery and freedom. They no longer had masters, but they did not have the rights of a free people,” Judge Gergel said. “Black Southerners routinely were denied the right to vote, were segregated physically from the dominant white society as a matter of law, and relegated to the margins of American prosperity. Racial violence and lynchings festered beneath the surface, ready to emerge at any moment.”

Attack on Sgt. Woodard Impacts the White House

Nearly 900,000 African-American veterans returned home after the end of World War II in 1945, most of them to the South. Many of these veterans were changed by their wartime experience, Judge Gergel said, and were not willing to suffer injustice and inequality quietly now that they were back home. But state governments were steadfast in their support of segregation, and the federal government largely was just a “passive bystander,” Judge Gergel said.

Something had to be done. But what? And by whom?

“Something had to be done. But what? And by whom?” he said.

The answers proved to be “A lot” and “By many.” The African-American press heavily covered the attack on Sgt. Woodard, and Orson Welles focused his national radio show on the incident. Mass protests took place in African-American neighborhoods across the country, and a benefit concert for Sgt. Woodard featured such luminaries as Cab Calloway, Nat King Cole and boxing champion Joe Louis. At the same time, other returning African-American military veterans experienced violence upon their return home.

“In 1946, a delegation of civil rights leaders met with President Harry Truman in the White House, deeply distressed by the wave of racial violence,” Judge Gergel said.

He said President Truman at first was reluctant to get involved in civil rights issues, given the pushback he knew would occur from powerful Southern lawmakers. But his mood changed when NAACP Executive Secretary Walter White, a close ally of the Truman Administration, shared Sgt. Woodard’s story.

“As the tragic story unfolded, Truman sat riveted and became visibly agitated at the idea of a uniformed, decorated American soldier being so cruelly treated,” Judge Gergel said. Just days later, a federal prosecutor charged Batesburg Police Chief Lynwood Shull with depriving Sgt. Woodard of his civil rights and a Presidential Committee on Civil Rights was organized. That committee produced a groundbreaking report which called for the end of segregation in the military. President Truman followed that recommendation and in 1948, during his re-election campaign, ordered that the US military was to be desegregated.

“The successful desegregation of the military was the beginning of the end of Jim Crow,” Judge Gergel said.

Sgt. Woodard Case Leads Charleston Judge to Become Civil Rights Advocate

Judge J. Waties Waring of Charleston also was greatly impacted by what happened to Sgt. Woodard in Batesburg. The wealthy son of a Confederate veteran and a descendant from a long line of slave owners, Judge Waring seemed to be an unlikely supporter of the burgeoning civil rights movement.

Judge Waring was assigned to oversee Shull’s federal trial. At first, he was skeptical about the federal government taking an active role in civil rights issues. But upon hearing Sgt. Woodard’s story, he was traumatized by the horrific incident and the greater reality it reflected.

The trial itself was largely a travesty, much to Judge Waring’s chagrin. The local prosecutor barely presented a case, calling the bus driver as his only witness, and later, Judge Waring said, “I was shocked by the hypocrisy of my government...in submitting that disgraceful case....” The all-white jury acquitted Shull in just 28 minutes.

“These were not subjects that could be discussed openly by white Charlestonians of that era,” Judge Gergel said. So Judge Waring and his wife, Elizabeth, began to seriously study and read about the effects of racism and segregation in private.

His evolving views on civil rights led Judge Waring in the 1947 case of Elmore v. Rice, which sought to overturn South Carolina’s long-standing practice of a whites-only Democratic Party primary.

“Judge Waring, when he was assigned the case, immediately appreciated that any decision recognizing the right of minority citizens to vote would produce intensely hostile, and possibly violent, public reaction,” Judge Gergel said. He and Elizabeth knew that if he did what he felt to be right, their lives would never be the same. Nevertheless, he ruled that whites-only primaries were unconstitutional. When political leaders attempted to deny the order, Judge Waring gathered them for an emergency meeting and informed them they would be jailed for contempt of court if they continued to violate his order.

An angry mob burned a cross on the Warings’ lawn, and they received a constant stream of death threats. But he continued his efforts by saying school segregation was illegal in 1951’s Briggs v. Elliott. The three-judge panel ruled 2-1 against the plaintiffs (who were represented by future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall). But the case was a vital precedent in building the ultimately successful effort to dismantle school segregation in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954—and drew a direct line between Sgt. Isaac Woodard’s bus ride and the landmark Brown v. Board decision.

Womble Bond Dickinson Columbia Office Managing Partner Kevin Hall and Charleston Office Managing Partner Jim Myrick provided introductory remarks for Judge Gergel’s presentation, which took place in the firm’s Charleston office.