This article originally was published at Law360.

Introduction

The authors have recently proposed alternative analyses for the discretionary denial of IPR and PGR petitions involved in parallel district court litigation,[1] as well as for the discretionary denial of serial petitions filed before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”).[2] The PTAB is also currently at a crossroads with yet a third similar but distinct issue—the discretionary denial of parallel petitions filed before the PTAB.[3] “Serial petitions” refer to multiple successive petitions challenging a particular patent that are filed by the same or different petitioners, whereas “parallel petitions” refer to multiple contemporaneous petitions challenging a particular patent that are filed by the same (or a related) petitioner. Although the PTAB has promulgated an analytical factor-based framework for evaluating the discretionary denial of serial petitions, the PTAB has not done so for parallel petitions. Rather, the Board has simply issued general guidance that provides APJ panels with exceedingly broad discretion, providing little predictability for the involved parties or other stakeholders. Thus, rather than propose an alternative analysis for parallel petitions (as the authors have proposed for serial petitions), the authors propose herein a novel factor-based analysis for considering the discretionary denial of parallel PTAB petitions, keeping in mind considerations such as fairness, predictability, consistency, and efficiency.

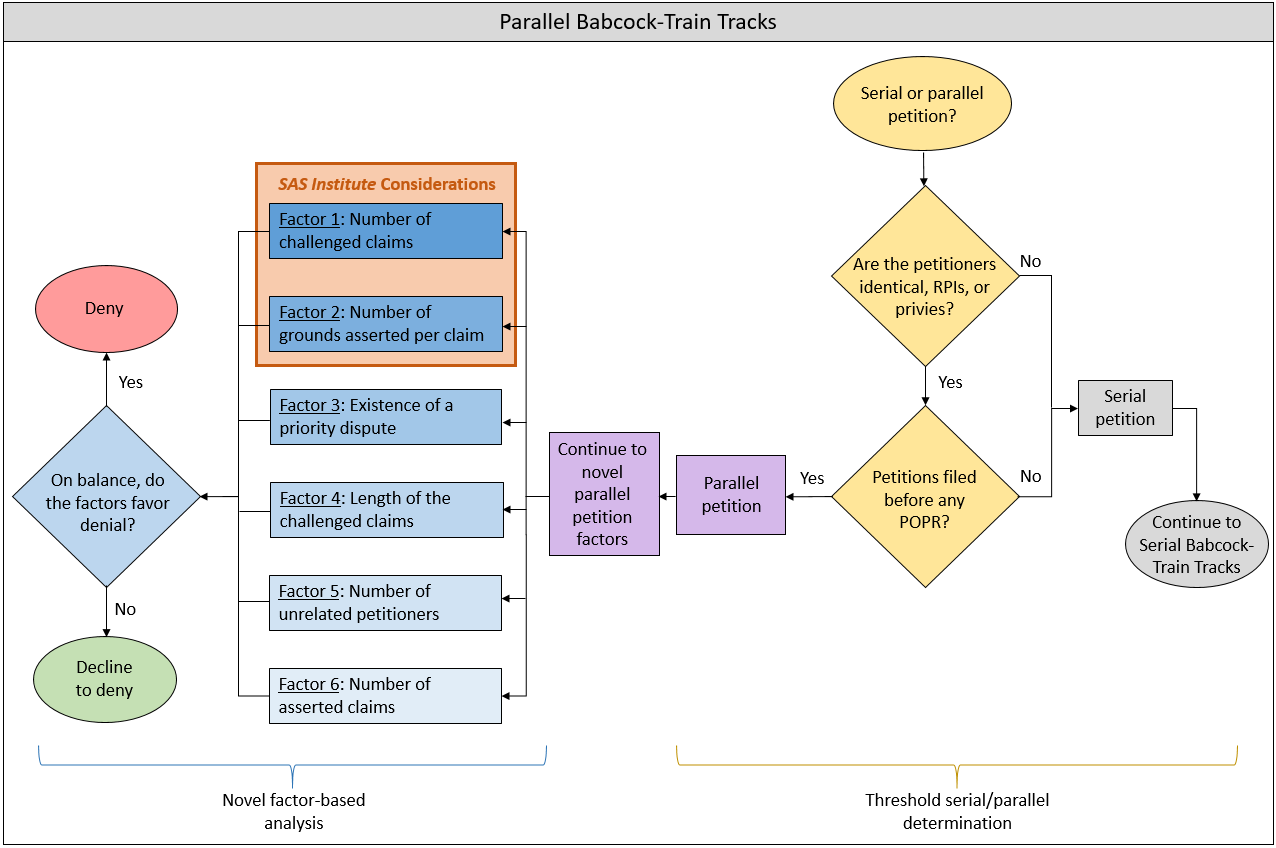

In an effort to begin a working dialogue focused on developing a factor-based analytical framework for the discretionary denial of parallel petitions, the authors propose a set of “Parallel Babcock-Train Tracks”[4] herein, which are intended to complement their earlier-proposed “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks”[5] for serial petitions, as well as the “Babcock-Train Factors” for petitions involved in parallel district court or ITC litigation.[6]

Parallel Petitions and the PTAB’s Updated Consolidated Trial Practice Guide

In the July 2019 Trial Practice Guide Update to the Consolidated Trial Practice Guide, the Board addressed parallel PTAB petitions challenging the same patent:

Based on the Board’s prior experience, one petition should be sufficient to challenge the claims of a patent in most situations. Two or more petitions filed against the same patent at or about the same time (e.g., before the first preliminary response by the patent owner) may place a substantial and unnecessary burden on the Board and the patent owner and could raise fairness, timing, and efficiency concerns.[7]

The Board also “recognize[d] that there may be circumstances in which more than one petition may be necessary, including, for example, when the patent owner has asserted a large number of claims in litigation or when there is a dispute about priority date requiring arguments under multiple prior art references.”[8] But the Board’s formal guidance for the discretionary denial of parallel petitions ends with those vague considerations.

Despite setting forth precedential, factor-based analyses for considering the discretionary denial of serial petitions in General Plastic,[9] and for considering the discretionary denial of petitions involved in parallel litigation in other tribunals in Apple v. Fintiv,[10] the Board has not promulgated a factor-based analysis for considering the discretionary denial of parallel petitions. Accordingly, to date, APJ panels are left with only the foregoing (very limited) guidance in the Trial Practice Guide Update when faced with evaluating the potential discretionary denial of parallel petitions.

In the authors’ view, the current vagueness creates troubling uncertainty for petitioners and patent owners alike, and places too much unfettered discretion in individual APJ panels rather than setting forth a consistent framework for the Board as an agency. Moreover, this vagueness creates troubling uncertainties for petitioners regarding whether they will be afforded an opportunity to have the merits of their patentability challenges considered by the Board, or whether another contemporaneously filed petition will wholly preclude those challenges. Given the front-loaded nature of PTAB proceedings—including lengthy and detailed petitions and in-depth technical declarations—a purely procedural denial typically results in a substantial waste of the petitioner’s resources (e.g., time and expense), contrary to the objectives of the AIA. Moreover, such a procedural denial may result in the dismissal of meritorious patentability challenges, also contrary to the goals of the AIA.

Accordingly, APJs and PTAB practitioners alike sorely need an analytical factor-based analysis that will provide considerably more certainty and consistency to the PTAB’s consideration of the discretionary denial of parallel PTAB petitions.

Proposed Factor-Based Analysis for Parallel Petitions: The “Parallel Babcock-Train Tracks”

Prior to engaging in a factor-based analysis, the Panel should first consider—as a threshold consideration—whether the petition at issue is a serial petition or a parallel petition. The first inquiry should ask whether the petitioners filing the petitions are identical, real parties-in-interest (“RPIs”), or privies. On its face, this inquiry may appear to be fairly benign, especially considering the Board’s explicit language in the Trial Practice Guide Update describing parallel petitions as “multiple petitions by a petitioner.”[11] But given the Board’s expansion of the concept of “same petitioner” from the General Plastic serial petitions analysis,[12] it is prudent that this inquiry be explicitly addressed at the outset of the analysis. If the petitioners are not identical, RPIs, or privies, then the Board should conclude that the petitions are not parallel and the analysis should proceed under the analytical framework for serial petitions.[13]

If the petitioners are identical, RPIs, or privies, then the next inquiry should ask whether the petitions were filed “at or about the same time,” again borrowing language from the description of parallel petitions in the Trial Practice Guide Update.[14] The Board provides as an example that “at or about the same time” is “before the first preliminary response by the patent owner.”[15] This timing—a little more than three months from the filing of the first petition[16]—is reasonable, because at that stage of the proceeding the petitioner has not gained any insight into the patent owner’s defenses and thus has gained no substantive or procedural advantage. So only if the petitions were filed before a patent owner preliminary response (“POPR”) has been filed in response to the earliest petition should the Board continue to the factor-based analysis for parallel petitions set forth below. Otherwise, the petitions should be considered serial and analyzed as such.[17]

Once the APJ panel has determined as a threshold matter that two or more petitions are parallel because a) they involve identical petitioners, RPIs, or petitioners in privity, and b) they were filed before submission of a POPR, the panel should then proceed to evaluate the set of non-exhaustive discretionary denial factors set forth below (in decreasing order of weight):

1.The Number of Challenged Claims

Guidance: The greater the number of claims that are challenged, the more this factor will weigh against discretionary denial, and vice versa. But, in conjunction with Factor 2, consider whether under SAS Institute the number of unmeritorious claim challenges supports discretionary denial of the petition under Section 314(a).

Commentary: This factor considers the number of claims challenged in the petition,[18] and attempts to balance between a patent owner’s strategic decision to prosecute a large number of claims in a given patent, and a petitioner’s strategic decision to challenge a large number of those claims before the PTAB. A patent owner should not be penalized for choosing to prosecute a large claim set, but conversely, that prosecution strategy should not immunize those claims from a PTAB challenge. Importantly, however, the PTAB’s SAS Institute guidance provides an “emergency brake” of sorts for petitions containing too many claims whose unpatentability challenges are not meritorious, permitting the panel to discretionarily deny the petition under 35 USC § 314(a).[19]

2. The Number of Grounds Per Challenged Claim

Guidance: The greater number of grounds for each challenged claim over three for an IPR, or over four for a PGR, the more this factor will weigh in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa. But, in conjunction with Factor 1, consider whether under SAS Institute the number of unmeritorious grounds supports discretionary denial of the petition under Section 314(a).

Commentary: To address the Board’s efficiency concerns for parallel petitions, this factor motivates a petitioner to focus its petition on the strongest unpatentability arguments, rather than taking a “shotgun” approach to the patent challenge. In connection with the other factors, this factor helps distinguish between efficient petitions that are lengthy simply because the petitioner has a lot territory to cover, versus inefficient petitions that are lengthy due to the petitioner’s verbosity and/or lack of focus.[20] The different word counts for an IPR petition (14,000 words)[21] versus a PGR petition (18,700 words)[22] presumably account for an additional ground for a PGR. Importantly, however, as with Factor 1, the PTAB’s SAS Institute guidance provides a failsafe for petitions containing multiple non-meritorious grounds, permitting the Panel to discretionarily deny the petition under 35 USC § 314(a).[23]

3. The Existence of a Priority Dispute for the Challenged Claims

Guidance: If the petition raises a priority dispute with respect to the challenged claims, this factor will weigh against discretionary denial.

Commentary: This factor appreciates the need for additional petition length if the petitioner raises a priority dispute with respect to the challenged claims. The Board has often considered a priority dispute to be a legitimate justification for a longer petition.[24] Note that this factor is effectively a one-way ratchet; absence of a priority dispute is the norm, and thus does not weigh in favor of discretionary denial.

4. The Length of the Challenged Claims

Guidance: The longer the challenged claims are by average word count, the more this factor will weigh against discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: This factor presumes that more written analysis will generally be required to challenge longer claims having more limitations. Conversely, shorter claims with fewer limitations generally require less written analysis. As a suggested benchmark, a “long” claim would be an independent claim of over 175 words or a dependent claim of over 40 words.[25] The larger the magnitude by which the length of the challenged claims, on average, is greater or less than these word counts, the heavier this factor will weigh for or against petition denial, respectively.

5. The Number of Unrelated Petitioners

Guidance: The greater the number of unrelated petitioners over one, the more this factor will weigh against discretionary denial.

Commentary: Multiple unrelated parties filing the same petition presents a likelihood that different parties (and their respective PTAB counsel) will have different strategies for the collective unpatentability challenges to pursue. The term “unrelated” is directed to legal affiliation, and not co-defendants in other legal proceedings. The PTAB should encourage multiple unrelated parties to join in a single petition, thereby increasing efficiency and reducing the likelihood of subsequent serial petitions. And fairness suggests that those parties may be provided with additional space to articulate their preferred analysis.[26] Because there must be at least one petitioner, this factor also works as a one-way ratchet—favoring institution for multiple unrelated parties, but being neutral for a sole petitioner.

6. The Number of Claims Asserted by the Patent Owner

Guidance: The greater the number of claims that are asserted by the Patent Owner, the more this factor will weigh against discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: Typically correlated to Factors 1 and 2 to a significant degree, this factor is intentionally placed at the end of the analysis in order to reduce the PTAB’s reliance on related litigation, which is subject to frequent and often dramatic changes and is difficult for the Board to accurately predict. Nonetheless, the Board has recognized that multiple petitions may be necessary “when the patent owner has asserted a large number of claims in litigation”.[27] But the Board should take pause before weighing the opposite in favor of petition denial because frequently patent lawsuits are filed only asserting a single representative patent claim at the pleading stage[28] (or in some instances, not expressly asserting any particular claim[29]), and then amended later through the course of the litigation to assert additional patent claims. Moreover, while the patent owner may have filed preliminary infringement contentions in the litigation, such contentions may later be amended—long after the petition has been filed—to assert additional claims. A petitioner should not be penalized for challenging all of the patent claims that it believes are unpatentable, regardless of whether those claims have been asserted (yet) by the patent owner.

The authors propose that the above factors in the “Parallel Babcock-Train Tracks” should be non-exhaustive, and thus the PTAB should not be prohibited from considering other non-enumerated factors when raised by the parties and as appropriate.

A general summary of the complete proposed analysis under the “Parallel Babcock-Train Tracks” is provided in the flowchart below:

Continued Dialogue

The authors’ proposal of the “Parallel Babcock-Train Tracks” attempts to articulate, for the first time, an analytical, factor-based framework for considering the discretionary denial of parallel PTAB petitions, weighing fairness, predictability, consistency, and efficiency concerns. It is likely that various stakeholders in the PTAB community will prefer additions, subtractions, and/or modifications to these factors. The authors welcome such a continuing dialogue and hope that this proposal can provide a helpful starting point for the ongoing discussion.

[1] See Babcock & Train, A Proposed Alternative to PTAB Discretionary Denial Factors, Law360 (Oct. 1, 2020) (hereinafter “Babcock-Train Factors”).

[2] See Babcock & Train, Creating a Better Framework for PTAB Serial Petition Denials, Law360 (Nov. 17, 2020) (hereinafter “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks”).

[3] U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, PTO-C-2020-0055, Request for Comments on Discretion to Institute Trials Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Oct. 20, 2020).

[4] The authors’ naming of these factors reflects that the entire analyses herein are solely the personal views of the authors, and should not be attributed in any way to Womble Bond Dickinson or any of its clients.

[5] See Serial Babcock-Train Tracks, supra note 2.

[6] See Babcock-Train Factors, supra note 1.

[7] U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Trial Practice Guide Update (July 2019) at 26.

[8] Id.

[9] Gen. Plastic Indus. Co., Ltd. v. Canon Kabushiki Kaisha, IPR2016-01357, Paper 19 (Sept. 6, 2017) (precedential, seven-APJ panel).

[10] Apple Inc. v. Fintiv, Inc., IPR2020-00019, Paper 11 (March 20, 2020) (precedential, designated May 5, 2020).

[11] Trial Practice Guide Update, supra note 7 at 26 (emphasis added).

[12] See Serial Babcock-Train Tracks, supra note 2.

[13] Id.

[14] Trial Practice Guide Update, supra note 7 at 26.

[15] Id.

[16] 37 C.F.R. §§ 42.107(b) & 42.207(b) (the POPR is due three months from the date of the formal PTAB notice according the petition a filing date).

[17] See Serial Babcock-Train Tracks, supra note 2.

[18] See Square, Inc. v. 4361423 Canada, Inc., IPR2019-01626, Paper 14 at 10 (Mar. 30, 2020) (“[T]here are only eighteen challenged claims, which generally is not a significantly large number of claims to address in a single petition, and Petitioner was able to assert multiple grounds against all eighteen challenged claims in a single petition.”).

[19] See PTAB, Guidance on the Impact of SAS on AIA Trial Proceedings (Apr. 26, 2018); see also SAS Q&As (June 5, 2018):

D3. Q: Will the Board institute a petition based on the percentage of claims and grounds that meet the reasonable likelihood standard, e.g., 50%?

A: No. The Board does not contemplate a fixed threshold for a sufficient number of challenges for which it will institute. Instead, the panel will evaluate the challenges and determine whether, in the interests of efficient administration of the Office and integrity of the patent system (see 35 USC § 316(b)), the entire petition should be denied under 35 USC § 314(a).

[20] See Chegg, Inc. v. NetSoc, LLC, IPR2019-01171, Paper 16 at 14 (Dec. 5, 2019) (“[W]e are not persuaded by Petitioner's argument that the Petitions differ materially because they ‘combine different references in different ways to arrive at the claimed limitations[.]’”).

[21] 37 C.F.R. § 42.24(a)(1)(i).

[22] 37 C.F.R. § 42.24(a)(1)(ii).

[23] See PTAB, Guidance on the Impact of SAS on AIA Trial Proceedings (Apr. 26, 2018); see also SAS Q&As (June 5, 2018):

D2. Q: In view of the Office’s policy to institute on all challenges or none, how will the Board handle petitions that contain voluminous or excessive grounds for institution in light of the Office’s policy of instituting on all claims?

A: The panel will evaluate the challenges and determine whether, in the interests of efficient administration of the Office and integrity of the patent system (see 35 USC § 316(b)), the entire petition should be denied under 35 USC § 314(a).

[24] Trial Practice Guide Update, supra note 7 at 26 (“[T]he Board recognizes that there may be circumstances in which more than one petition may be necessary, including, for example, . . . when there is a dispute about priority date requiring arguments under multiple prior art references.”); Chegg, Paper 16 at 14 (“[W]e are persuaded by Petitioner that Patent Owner may antedate multiple references in this proceeding”); 10X Genomics, Inc. v. Bio-Rad Labs., Inc., IPR2020-00086, Paper 8 at 53-54 (Apr. 27, 2020) (“To avoid institution of two parallel petitions, Patent Owner could have agreed not to dispute Petitioner’s contention that the Ismagilov references are prior art to the ’837 Patent, thereby eliminating Petitioner’s alleged difference between the 086 and 087 Petitions.”).

[25] See Osenga, The Shape of Things to Come: What We Can Learn from Patent Claim Length, 28 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 617, 632-33 (Jan. 3, 2012) (explaining that, between 1958-2007, the average number of words per independent claim was 175.1253, and the average number of words per dependent claim was 41.22297).

[26] See Chegg, Paper 16 at 14 (“[W]e are persuaded by . . . Petitioner's submission of only two Petitions on behalf of three petitioners representing seven real parties-in-interest leads to an efficient administration of the proceedings.”).

[27] Trial Practice Guide Update, supra note 7 at 26.

[28] Atlas IP LLC v. Pac. Gas & Elec. Co., No. 15-CV-05469-EDL, 2016 WL 1719545, at *5 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 9, 2016) (“Iqbal and Twombly only require Plaintiff to state a plausible claim for relief, which can be satisfied by adequately pleading infringement of one claim.”).

[29] Incom Corp. v. Walt Disney Co., No. CV15-3011 PSG (MRWX), 2016 WL 4942032, at *3 (C.D. Cal. Feb. 4, 2016) (“Plaintiff has stated a plausible claim for direct infringement by specifically identifying Defendants’ products and alleging that they perform the same unique function as Plaintiff's patented system.”).