This article originally was published at Law360.

Introduction

In 2012, Congress enacted the American Invents Act (“AIA”) for the purpose of “establish[ing] a more efficient and streamlined patent system that will improve patent quality and limit unnecessary and counterproductive litigation costs.”1 Not long thereafter, the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (“PTAB”) confronted the practice of serial petitioning—a given petitioner filing a second PTAB petition challenging the same patent as challenged in an earlier unsuccessful PTAB petition.2 In a 2017 precedential decision, the Board provided a framework for the discretionary denial of serial petitions, attempting to reconcile the goals of the AIA with “the potential for abuse of the review process by repeated attacks on patents.”3 The Board’s analysis began with the simple question of “whether the same petitioner previously filed a petition directed to the same claims of the same patent.”4 However, subsequent PTAB decisions have contorted the meaning of the “same petitioner” for purposes of the serial petition analysis. What began as an attempt to limit petitioners to a single bite at the proverbial apple has since been expanded to prevent different (and sometimes entirely unrelated) petitioners from even having a first bite. In order to conform with the goals of the AIA, this unwarranted expansion should be curbed and the analysis for discretionary denial of serial petitions should be modified.

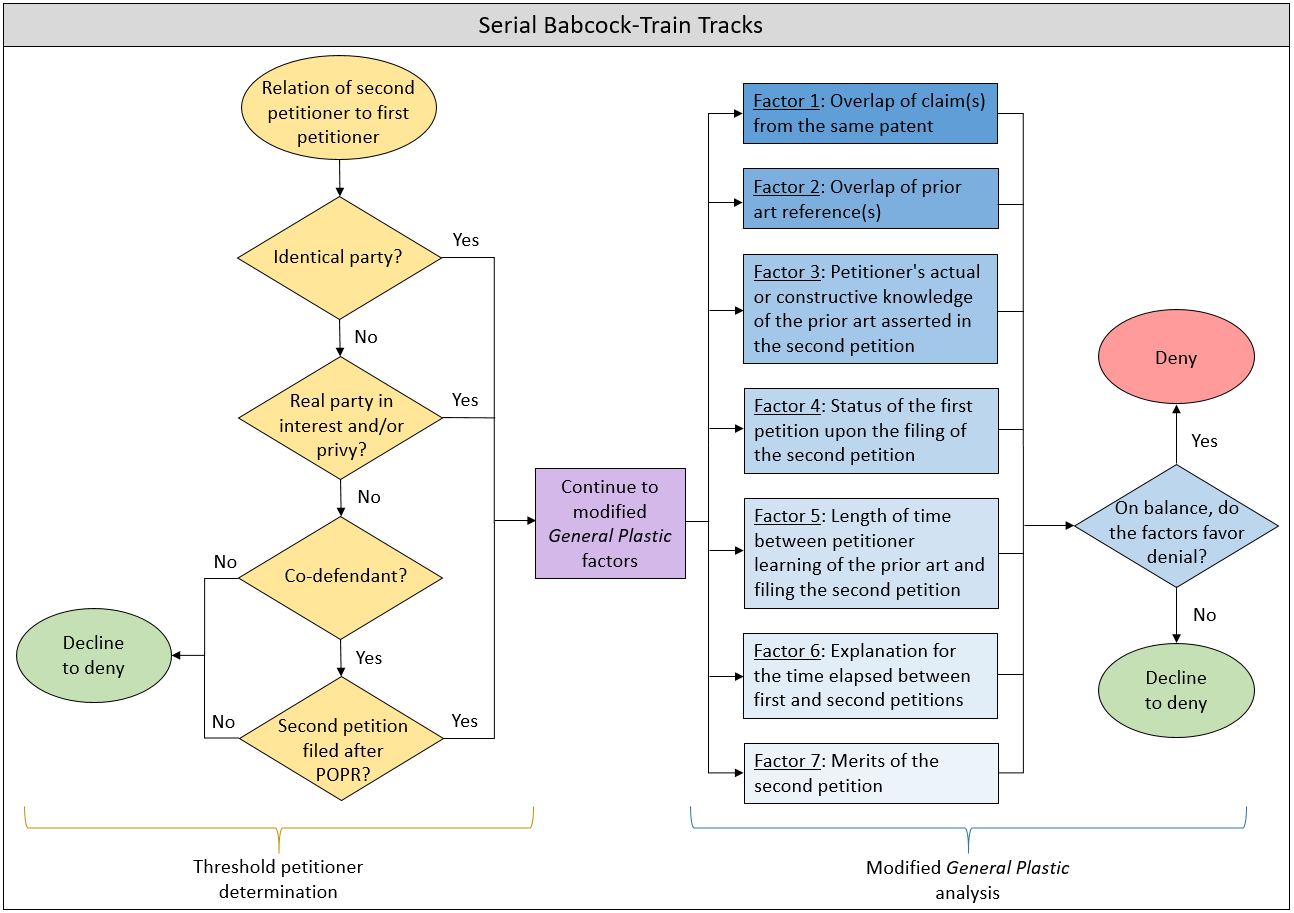

In an effort to add constructive commentary and aid in developing a more comprehensive and neutral framework,5 the authors set forth a proposed alternative analysis to the PTAB’s current General Plastic factors, which the authors term the “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks”.6

General Plastic

In the Board’s precedential General Plastic decision, the Board promulgated the following seven factors (originally set forth in NVIDIA v. Samsung7) for considering the Board’s discretion to deny so-called “follow-on” or serial petitions:

- whether the same petitioner previously filed a petition directed to the same claims of the same patent;

- whether at the time of filing of the first petition the petitioner knew of the prior art asserted in the second petition or should have known of it;

- whether at the time of filing of the second petition the petitioner already received the patent owner’s preliminary response to the first petition or received the Board’s decision on whether to institute review in the first petition;

- the length of time that elapsed between the time the petitioner learned of the prior art asserted in the second petition and the filing of the second petition;

- whether the petitioner provides adequate explanation for the time elapsed between the filings of multiple petitions directed to the same claims of the same patent;

- the finite resources of the Board; and

- the requirement under 35 U.S.C. § 316(a)(11) to issue a final determination not later than 1 year after the date on which the Director notices institution of review.8

The Board developed these so-called “General Plastic factors” because both the General Plastic and NVIDIA cases involved identical petitioners.9 Not surprisingly, then, each of these cases raised the specter of a potentially unwarranted “second bite at the apple”. Notably, the first factor set forth two critical considerations, namely: 1) same petitioner; and 2) same claims of the same patent. Importantly, these factors were specifically developed in the context of the “same petitioner” and “same claims” facts of General Plastic and NVIDIA, but subsequent cases have greatly expanded this language to encompass different (and even unrelated) petitioners. In the authors’ view, this unwarranted expansion has frustrated the intent of the AIA and has overcorrected the Board’s aim of remedying the perceived “abuse of the review process”.

Valve I & II

In Valve I, the Board elaborated that it considered any relationship between petitioners when weighing the General Plastic factors.10 Subsequently in Valve II, the Board weighed Factor 1 against institution where the second petitioner was not the same as the earlier petitioner, but 1) had joined a previously instituted IPR, and 2) had been voluntarily dismissed as former co-defendant in a district court action with the earlier petitioner.11 This Valve II decision represented an expansion of the scope of Factor 1’s inquiry into the “same petitioner”, now encompassing related petitioners who face discretionary dismissal based on a previously filed petition.

Expansion Beyond General Plastic and Valve I & II

After the Board’s decisions in Valve I & II to treat different but related petitioners as the “same petitioner” for purposes of the General Plastic factors, subsequent panels have relied upon this precedent to extend the Factor 1 consideration of the “same petitioner” even further to wholly unrelated petitioners. In Ericsson v. Uniloc, the Board acknowledged, “[i]t seems clear that Petitioner is not a co-defendant with the prior petitioners” and “absent this petition, no [significant] relationship [with the other petitioners], on the record before us, existed.” Nonetheless, the Board still weighed General Plastic Factor 1 against institution because “[t]he instant Petitioner’s decision to use the prior petitions as a roadmap for its own petition ties the interests of all the petitioners together.”12

Thus, like a game of telephone, the Board has distorted the Factor 1 consideration from the “same” petitioner in General Plastic, to a “related” petitioner in Valve I & II, and finally to essentially “any” petitioner in Ericsson. As evidence that this morphed analysis is not a natural expansion of the goals of the AIA or the Board’s initial objectives in General Plastic and NVIDIA, the determination of all petitioners as the “same petitioner” places an undue strain on the remaining analysis. For example, in United Fire v. Engineered Corrosion, the Board exercised its discretion to deny a petition in light of previously filed petitions, but “[b]ecause Petitioner was not a petitioner in the prior proceedings,” the Board was compelled to disregard Factors 2 and 4 as “ha[ving] little probative value here.”13

The Board’s unwarranted expansion of the General Plastic factors creates troubling uncertainties for petitioners regarding whether they will be afforded an opportunity to have the merits of their patentability challenges considered by the Board, or whether another party’s previously filed petition will wholly preclude those challenges. Given the front-loaded nature of PTAB proceedings—including lengthy and detailed petitions and in-depth technical declarations—a purely procedural denial typically results in a substantial waste of the petitioner’s resources (e.g., time and expense), contrary to the objectives of the AIA. Moreover, such a procedural denial may result in the dismissal of meritorious patentability challenges, also contrary to the goals of the AIA.

Further, even the treatment of related petitioners as the same petitioner raises serious fairness concerns because, as explained in Toshiba v. Walletex, even where “all of the Petitioners are co-defendants in related district court litigation, they remain distinct parties, with ultimately distinct interests, and distinct litigation strategies.”14 There can be no legitimate dispute that petitioners (and their PTAB counsel) come in all shapes and sizes, which can create wide variability in the quality, strategy, and persuasiveness of PTAB petitions. For example, a patentee may first strategically sue a small defendant, who has limited resources and may be expected to file an ineffective petition challenging the asserted patent. This strategy may thus serve to procedurally “inoculate” that patent against a subsequent defendant, who may have considerably more resources to expend on the challenge (e.g., prior art searches, expert witnesses, and PTAB counsel).

In balancing the equities, patent owners complain of their perceived unfairness in allowing multiple attacks against the same patent. But this concern often evaporates when “the volume appears to be a direct result of [the petitioners’] own litigation activity.”15 Indeed, a patent owner should not expect to poke a sleuth of sleeping bears and hope to only face a single counter-attack. Furthering that analogy, choosing to poke a bear cub first should not preclude mama bear’s attack after she is also poked.

Additional Concerns with the General Plastic Factors

Although the expansion of Factor 1 likely represents the most significant concern with the General Plastic factors, the authors also address secondary concerns with respect to others of those factors.

In an attempt to prevent a petitioner from using the first petition as a so-called “roadmap,”16 the Factor 3 inquiry looks at whether, at the time of filing of the second petition, the petitioner already received 1) the patent owner’s preliminary response (“POPR”) to the first petition, or 2) the Board’s decision on institution (“DI”) in the first proceeding. But it is unclear why the inquiry ends at the DI, where receiving a final written decision (“FWD”) would further the concern of the petitioner using the first proceeding as a “roadmap”. Indeed, the Board has considered situations where a FWD had been issued in the first proceeding before the filing of the second petition as a Factor 3 component weighing strongly in favor of petition denial.17

Factors 6 and 7, which ask about the finite resources of the Board and the Board’s requirement to issue a final determination under 35 U.S.C. § 316(a)(11), respectively, are frequently coupled together by the Board as a single consideration.18 These factors are similar in that they both inquire into generic circumstances relating to the Board, rather than to the parties or the specific facts of a given case. The Congressional focus on an “efficient and streamlined patent system” was concerned with limiting unnecessary and counterproductive litigation costs for the parties, not preserving the Board’s “finite resources.” As such, these factors shift the focus in the wrong direction—away from circumstances relating to the parties and the case-at-issue, and toward general circumstances relating to the Board’s everyday administration of its case load. If balanced properly, the other party-related factors should be sufficient to have the indirect effect of preserving the Board’s finite resources by discerning between legitimate and wasteful serial petitions. Moreover, by including these indeterminate and effectively “catch-all” factors, the Board’s discretion becomes essentially unbounded and the predictability of institution decisions is largely eliminated.

Proposed Alternative to the General Plastic Analysis: The “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks”

At the outset, the authors do not consider the original intent of the General Plastic factors to be flawed for their primary goal of curtailing “abuse of the review process by repeated attacks on patents.”19 Rather, it is the Board’s subsequent expansion of these factors—particularly its assessment of whether the same petitioner is bringing a subsequent petition—that gives rise to the need for a more neutral and AIA-focused alternative analysis. With some modifications, many of the General Plastic factors can be preserved as part of an analysis that is more aligned with Congressional intent.

The authors first propose bifurcating the two distinct considerations within Factor 1 into a threshold consideration, such that the issues of “same petitioner” and “same claims of the same patent” are assessed initially and separately. The former should be taken as a preliminary consideration, and the latter should represent the entirety of a modified Factor 1, if the threshold inquiry is met.

Prior to engaging in a factor-by-factor analysis, the Board should first consider the relationship, if any, of the current petitioner with the previous petitioner. If they are the same party, privies, or real parties-in-interest, then the threshold inquiry is satisfied, and the Board should proceed to the factor analysis. Alternatively, if the petitioners are related only as co-defendants in a district court or ITC litigation, then the threshold inquiry is met only if the later petition was filed after the POPR in the previous proceeding, effectively giving the second petitioner three months to file a second petition. Time-barring co-defendants in this manner addresses patent owners’ concerns of follow-on petitioners gaming the system by waiting to review the first POPR before filing a second petition, but also affords expeditious co-defendant petitioners an opportunity to file a separate petition without fear of procedural prejudice simply because another co-defendant filed its petition earlier. Finally, where the petitioners are unrelated by privity, real party-in-interest, or litigation, the threshold will not be met and the analysis ends. Again, a patent owner defending against multiple attacks by unrelated petitioners faces a problem of its own making. So the authors submit that this rule, while decisive, strikes a fair balance between petitioners’ access to PTAB review proceedings, on the one hand, and petitioners’ abuse of the review process, on the other, as the Board sought to do in General Plastic.

If, and only if, the foregoing threshold determination has been met, then the Board should continue to balance a modified version of the General Plastic factors. The authors propose that the PTAB de-designate the General Plastic factors as precedential authority,20 and adopt an alternative set of non-exhaustive discretionary denial factors as follows (in decreasing order of weight):

1) The Overlap of the Claim(s) Challenged in the First and Second Petitions

Guidance: The greater the overlap of at least one claim challenged in the first and second petitions, the more this factor will weigh in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: This factor represents the latter portion of the bifurcated General Plastic Factor 1. As a refinement, the consideration of the overlap between “claim(s)” expressly acknowledges that even a single overlapping claim would weigh in favor of denial. This is especially so when an overlapping claim is an independent claim.

2) The Overlap of the Prior Art Reference(s) Asserted in the First and Second Petitions

Guidance: The greater the overlap of at least one the prior art reference challenged in the first and second petitions, the more this factor will weigh in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: Similar to Factor 1, the consideration of the overlap between “prior art reference(s)” expressly acknowledges that even a single overlapping reference would weigh in favor of denial. This is especially so when the overlapping prior art reference is the primary reference and any non-overlapping reference is cumulative and/or purportedly discloses well-known features.

3) The Petitioner’s Actual or Constructive Knowledge of the Prior Art References Asserted in the Second Petition at the Time of Filing the First Petition

Guidance: If the petitioner knew or should have known of at least one of the prior art references asserted in the second petition at the time of filing the first petition, then this factor will weigh in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: A near adoption of General Plastic Factor 2, this factor limits the petitioner’s ability to game the system by withholding prior art references in a first petition, only to assert them in a subsequent petition and argue that there is little or no overlap of the asserted references. Where an asserted reference was not actually known but was publicly available at the time of the filing of the first petition, the petitioner will be charged with “constructive knowledge” of the references, following the jurisprudence that has been developed for estoppel under the “should have known” standard.

4) The Status of the First Petition upon the Filing of the Second Petition

Guidance: Filing the second petition after the following events have occurred in the first petition will weigh in favor of discretionary denial (in decreasing order of weight): issuance of FWD; issuance of DI; filing of POPR.

Commentary: A refinement of General Plastic Factor 3, this factor provides two improvements: 1) expressly considering whether a FWD has been issued; and 2) providing explicit guidance to increase the weight of this factor as the status of the first petition progresses. The more information that the petitioner has at its disposal when filing the second petition (especially when that information reveals the Board’s views with respect to the first petition), the greater the concern will be that the petitioner can use the first petition as a “roadmap.”

5) The Length of Time that has Elapsed Between the Time the Petitioner Learned of the Prior Art Asserted in the Second Petition and the Filing of the Second Petition

Guidance: The longer a petitioner waits to file the second petition after learning of the asserted prior art, the more this factor will weigh in favor of discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: This factor is an adoption of General Plastic Factor 4. The inclusion of the petitioner’s knowledge in this factor is not intended to affect the PTAB’s limited discovery practices and public disclosure requirements.

6) The Explanation for the Time Elapsed Between the Filing of the Second Petition and the Filing of the First Petition

Guidance: A reasonable explanation for the time delay between the filing of the two petitions will weigh against discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: A near adoption of General Plastic Factor 5, this factor has been modified to remove the amorphous standard of “adequate” and the binary “yes-or-no” determination. This revised language recognizes the likelihood of differing strengths of explanations.

7) The Merits of the Second Petition

Guidance: A strong petition on the merits will weigh against discretionary denial, and vice versa.

Commentary: A newly proposed consideration, this factor inquires into the substantive merits of the second petition.21 This merits-focused factor addresses Congress’ public policy concern of “improv[ing] patent quality” by allowing especially strong petitions to proceed with PTAB review.

The authors propose that the above factors in the “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks” should be non-exhaustive, and thus the PTAB should not be prohibited from considering other non-enumerated factors when raised by the parties and as appropriate.

A general summary of the complete proposed alternative analysis is provided in the flowchart below:

Continued Dialogue

The authors’ proposal of the “Serial Babcock-Train Tracks” attempts to rectify a primary concern of the PTAB’s unwarranted expansion of the General Plastic “same petitioner” analysis, and also endeavors to refine the remaining analysis to better conform with Congress’ intent in enacting the AIA. It is likely that various stakeholders in the PTAB community will raise additional concerns with regard to these factors and/or propose alternative solutions to the concerns presented herein. The authors welcome such a continuing dialogue and hope that this proposal can provide a helpful starting point for the ongoing discussion.

1 H.R. Rep. No. 112-98, pt. 1, at 40 (2011), 2011 U.S.C.C.A.N. 67, 69.

2See Conopco, Inc. v. Proctor & Gamble Co., IPR2014-00628, Paper 21 (PTAB Oct. 20, 2014).

3General Plastic Indus. Co., Ltd. v. Canon Kabushiki Kaisha, IPR2016-01357, Paper 19 (PTAB Sept. 6, 2017) (precedential, seven-APJ panel).

4Id. at 16.

5 This issue has recently received particular attention from the USPTO. See U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, PTO-C-2020-0055, Request for Comments on Discretion to Institute Trials Before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (Oct. 20, 2020).

6 The authors’ naming of these factors reflects that the entire analyses herein are solely the personal views of the authors, and should not be attributed in any way to Womble Bond Dickinson or any of its clients.

7 NVIDIA Corp. v. Samsung Elec. Co., IPR2016-00134, Paper 9 (May 4, 2016).

8General Plastic, Paper 19 at 9-10.

9Id. at 2-3 (“Nine months after the filing of the first set of petitions, Petitioner filed follow-on petitions against the same patents”); NVIDIA, Paper 9 at 8 (“The instant Petition is the second petition filed by Petitioner challenging claims 1-8 and 10-15 of the ’675 patent”).

10Valve Corp. v. Electronic Scripting Products, Inc., IPR2019-00062, Paper 11 (Apr. 2, 2019) (“Valve I”).

11 Valve Corp. v. Electronic Scripting Products, Inc., IPR2019-00064, Paper 10 (May 1, 2019) (“Valve II”) (precedential).

12 Ericsson Inc. v. Uniloc 2017, LLC, IPR2019-01550, Paper 8 at 12 (Mar. 17, 2020).

13United Fire Protection Corp. v. Engineered Corrosion Sols., LLC, IPR2018-00991, Paper 10 at 13 (Nov. 15, 2018) (Regarding Factor 2, “[b]ecause Petitioner was not a petitioner in the prior proceedings challenging the ’700 patent, we conclude that whether Petitioner knew of or should have known of the asserted references at the time the prior petitions were filed has little probative value here.”); id. at 16 (Regarding Factor 4, “[a]s discussed above regarding Factor 2, the record does not establish when Petitioner learned of the asserted prior art. As such, we cannot determine, with any certainty, the length of time that elapsed between when Petitioner learned of the asserted prior art and the filing of the Petition.”).

14 Toshiba Am. Info. Sys., Inc. v. Walletex Microelectronics Ltd., IPR2018-01538, Paper 11 at 22 (Mar. 5, 2019).

15Toshiba, Paper 11 at 21-22; see also Samsung Elecs. Co. v. Iron Oak Techs., LLC, IPR2018-01554, Paper 9 (Feb. 13, 2019) (The Board, when evaluating the General Plastic factors, “decline[d] to wield [Patent Owner’s] litigation activities as a shield.”).

16See General Plastic, Paper 19 at 17 (“The absence of any restrictions on follow-on petitions would allow petitioners the opportunity to strategically stage their prior art and arguments in multiple petitions, using our decisions as a roadmap, until a ground is found that results in the grant of review.”).

17United Fire, Paper 10 at 13 (“Patent Owner’s Response, Patent Owner’s expert testimony, and the Board’s Final Written Decision in the prior proceeding were also available when the Petition was filed.”).

18See, e.g., Valve I, Paper 11 at 15; Valve II, Paper 10 at 15-18; Toshiba, Paper 11 at 21.

19General Plastic, Paper 19 at 17.

20 See Quinn, USPTO Announces That PTAB Precedential Decisions Can Be Anonymously Nominated, IPWatchdog (Sept. 25, 2020).

21See Babcock & Train, A Proposed Alternative to PTAB Discretionary Denial Factors, Law360 (Oct. 1, 2020) (proposed Babcock-Train Factor 2).